This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 4. Here is a link to the overview of book 3 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 4 of the Iliad moves away from the dominant interests of book 3 in providing a kind of ‘flashback’ to the beginning of the Trojan War to the beginning of the violence in this poem. Where book 3 introduces the duel between Paris and Menelaos, book 4 turns back to Agamemnon’s leadership and the beginning of proper Iliadic violence. To ‘begin’ yet again, the scene returns to Zeus with the other gods on Olympos pondering not destroying Troy. Of course, the notion of preserving Troy is impossible, but this motif reinforces Zeus’ position as the ringmaster. As Bruce Heiden explores in a series of articles (see the bibliography before), Zeus’ speeches both outline the plot to come in the epic and provide guidelines for where the books break and how performances of the whole song may have been structured.

In my view on the reading and teaching and my general sense of the five major themes, book 4 is most engaged with the themes of politics, the relationship between gods and humans, and the positioning of Iliadic content and themes in and against other narrative traditions.

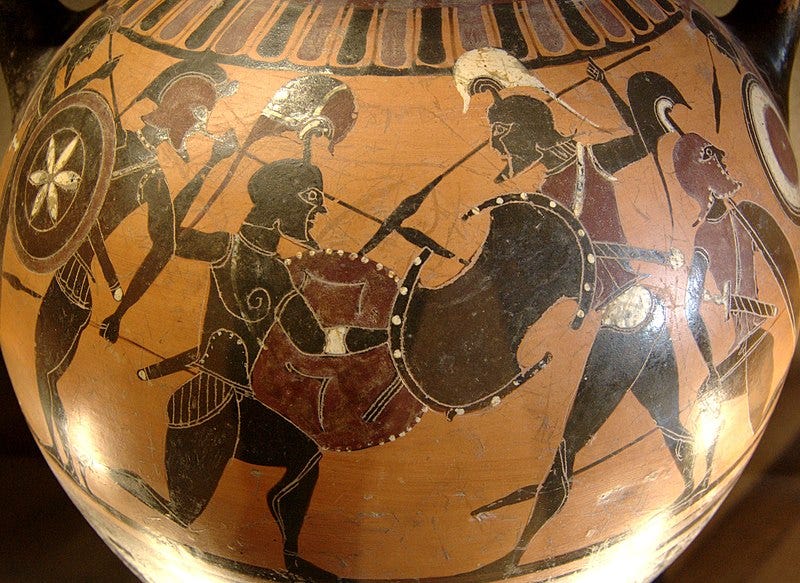

Zeus’ ‘stage-managing’ of the plot is an important part of the theme of divine will vs. human agency. Book 4 takes pains to (more firmly) establish the Trojans as oath-breakers, responsible for the conflict (as if we needed more reasons!). The initial argument between Zeus, Athena, and Hera, moreover, anticipates similar re-articulations of the plot in book 8 and echoes of theomachy in books 5, 8, 13, 14, and 15.

The central framing mechanism of book 4 is the so-called Epipōlēsis (ἐπιπώλησις) . The epipolesis (perhaps best translated as “the inspection of the troops” or something like that) is one of those episodes named specifically by ancient scholars. It denotes Agamemnon’s actions in book 4 when he goes around exhorting Idomeneus, the two Ajaxes, Nestor, Odysseus, and then finally Diomedes and Sthenelos. Elton Barker and I have written about this scene a few times, but I think Rachel Lesser puts it well when she argues in chapter four of her Desire in the Iliad that the epipolesis “may be the only scene in the Iliad where Agamemnon practices effective leadership.”

Indeed, along with actions in book 11, where Agamemnon enjoys his own aristeia, book 4 is one of the chief places where he is characterized both as a leader and as a brother (when Menelaos is wounded). But part of what makes this sequence interesting is that Agamemnon is at times somewhat inept at his task. Odysseus gets annoyed with him; the Ajaxes just nod and go on their way. But when he lays into Diomedes to shame him for not fighting (when he is on his way, he tells a story about Dioemdes’ father Tydeus that doesn’t make a lot of sense for the world of Homer. In this paradeigma, Agamemnon provides another example of a Homeric hero trying to make sense of his experiences through stories from the past and coming up short. As I see it, these are moments where the epic itself models the problems of paradigmatic thinking by exploring the limits of different stories’ analogical value. ( This is covered a little in the post Speaking of Centaurs.)

But as Elton Barker and I talk about in Homer’s Thebes and our article “On not Remembering Tydeus”, this moment is also central to the Iliad’s appropriation from other traditions in order to establish itself as the best story in town. Note how Sthenelos, in responding to Agamemnon, argues that he and Diomedes are better than their fathers:

“Ἀτρεΐδη, μὴ ψεύδε ᾿ ἐπιστάμενος σάφα εἰπεῖν·

ἡμεῖς τοι πατέρων μέγ᾿ ἀμείνονες εὐχόμεθ᾿ εἶναι·

ἡμεῖς καὶ Θήβης ἕδος εἵλομεν ἑπταπύλοιο

παυρότερον λαὸν ἀγαγόνθ᾿ ὑπὸ τεῖχος ἄρειον,

πειθόμενοι τεράεσσι θεῶν καὶ Ζηνὸς ἀρωγῇ·

κεῖνοι δὲ σφερέτῃσιν ἀτασθαλίῃσιν ὄλοντο·

τὼ μή μοι πατέρας ποθ᾿ ὁμοίῃ ἔνθεο τιμῇ.”

“Son of Atreus, don’t lie when you know how to speak truly. We claim to be better than our fathers: we took the foundation of seven-gated Thebes though we led a smaller army before better walls because we were trusting the signs of the gods and Zeus’ help. Those men perished because of their own recklessness. Don’t put our fathers in the same honor.”

This scene is somewhat unique in an epic that privileges the past as a place where men were greater than they are today. It capitalizes upon Sthenelos and Diomedes’ status as warriors who actually sacked Thebes to question whether the good old days were anything but merely old.

So, when reading book 4, pay close attention to how these speeches fulfill multiple tasks: they supercharge the plot, provide essential opportunities to characterize individual heroes, and give us a glimpse into how the Iliad pillages other traditions to foreground its own interests.

Some guiding questions for book 4

What does Zeus’ speech at the beginning of the epic do?

What is the cumulative effect of Agamemnon’s epipolesis (his rallying of the troops?)

What is the impact of the exchange between Diomedes, Sthenelus, and Agamemnon?

Brief Bibliography on the epipolesis and Agamemnon

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Christensen, Joel P., and Elton T. E. Barker. “On Not Remembering Tydeus: Agamemnon, Diomedes and the Contest for Thebes.” Materiali e Discussioni per l’analisi Dei Testi Classici, no. 66 (2011): 9–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41415488.

Donlan, Walter. “Homer’s Agamemnon.” The Classical World 65, no. 4 (1971): 109–15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4347609.

Haft, Adele J. “Odysseus’ Wrath and Grief in the ‘Iliad’: Agamemnon, the Ithacan King, and the Sack of Troy in Books 2, 4, and 14.” The Classical Journal 85, no. 2 (1989): 97–114. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3297409.

Hawkins, Anne Hunsaker. "Confronting Mortality: The Iliad's Androktasiai." Literature and Medicine 17, no. 2 (1998): 181-196. https://doi.org/10.1353/lm.1998.0022.

Heiden, B. (1996). The three movements of the iliad. Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 37(1), 5-22. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/three-movements-iliad/docview/229178418/se-2

Holmes, B. (2007). The Iliad's Economy of Pain. Transactions of the American Philological Association 137(1), 45-84. https://doi.org/10.1353/apa.2007.0002.

Kelly, Gordon P. "Battlefield Supplication in the Iliad." Classical World 107, no. 2 (2014): 147-167. https://doi.org/10.1353/clw.2013.0132.

Andrew Porter, Agamemnon, the pathetic despot: reading characterization in Homer. Hellenic studies series, 78. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019. 264 p.. ISBN 9780674984455 $24.95 (pb).

Ready, Jonathan L. "Toil and Trouble: The Acquisition of Spoils in the Iliad." Transactions of the American Philological Association 137, no. 1 (2007): 3-43.

Roisman, Hanna M. “Nestor the Good Counsellor.” The Classical Quarterly 55, no. 1 (2005): 17–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3556237.

Sammons, B. (2009). BROTHERS IN THE NIGHT: AGAMEMNON & MENELAUS IN BOOK 10 OF THE ILIAD. Classical Bulletin, 85(1), 27-47. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/brothers-night-agamemnon-amp-menelaus-book-10/docview/1401480000/se-2

Sammons, Benjamin. “The Quarrel of Agamemnon & Menelaus.” Mnemosyne 67, no. 1 (2014): 1–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24521943

Juan Carlos Iglesias Zoido. 2007. “The Battle Exhortation in Ancient Rhetoric.” Rhetorica 25: 141-158.

Posts so far

Preparatory Posts

Five Major Themes to Follow in the Iliad

Book-by-book students

The Plan: Zeus’ Plan in the Iliad

Prophet of Evils: Reading Iphigenia in and out of the Iliad

Speaking of Centaurs: Paradigmatic Problems in book 1

Thersites’ Body: Description, Characterization, and Physiognomy in book 2