This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 11. Here is a link to the overview of book 10 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 11 of the Iliad returns us to the violence of war and begins one of the longest sequences of battle in ancient literature: although there are moments of respite and distraction, day 19 of the Iliad takes us from dawn at the start of book 11 and goes until dusk at the end of book 19. Counting inclusively, this means that one full third of the epic, a battle sequence that includes the death of Patroklos and the struggle over his body, corresponds to one bloody day on the plains before Troy.

As I see it, the action of this book falls into three very different scenes: the conflict renewed by Zeus, resulting in the wounding of all the major Greek leaders; a brief return to Achilles where we see him responding to their suffering with concern, sending Patroklos to investigate; the long speech Nestor offers to try to persuade Patroklos to convince Achilles to return to war (or come himself in Achilles’ place). Patroklos does not return to report back to Achilles until the beginning of book 16

The plot of this book engages critically with the major themes I have noted to follow in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions, but the central themes I emphasize in reading and teaching book 11 are Family & Friends and Narrative Traditions.

Diomedes’ Foot Wound, And a Digression about Monro’s Law

As I have discussed in other posts, part of the art of the Iliad is how it integrates into its narrative arc motifs, scenes, and even episodes that belong to different parts of the Trojan War timeline. There are different ways to view this: the way Elton Barker and I have long thought about it is that the performance of mythical narrative was an essentially competitive market and the Homeric epics developed near the end of a performance tradition that both relied on repeated structures for complex compositions and prized the appropriation of narrative structures and details from rival traditions.

In establishing itself as the final epic about the war at Troy, the Iliad endeavors to tell the whole story of the war. This helps us to understand Homeric anachronisms, like the integration of episodes proper to the beginning of the whole conflict to the beginning of the story of the 9th year of the war (e.g., the catalogue of ships, the teichoskopia, the dual between Paris and Menelaos, the building of the Greek fortifications). There are somewhat fewer clear adaptations of episodes subsequent to the death of Hektor, but we have already seen in book 7 mention of the destruction of the walls around the ships and earlier in 6 echoes of the future death of Astyanax.

There’s a ‘law’ about Homeric representation (Monro’s Law, perhaps better called Niese’s) that goes something like this in its simplest form: the Homeric epics do not directly refer to actions contained in each other; the Odyssey will frequently refer to prior events of the Trojan War. D. B. Monro added that the Odyssey appears to demonstrate “tacit recognition” of the Iliad, while the Iliad reveals almost no recognition of the events of Odyssey. Scholars have often taken this observation to help support arguments for the later composition of the Odyssey.

I suspect that if we tally up references to narratives outside the scope of each epic we would find instead that both display a marked tendency to refer to antecedent events and only limited, often occluded knowledge of any futures. I think that rather than being an indication of later composition, this is a reflection of human cognition, a limited sense of realism that roots each epic in its own events but makes the stories before them active motifs in informing and shaping the narrative at hand. This is, I suggest, an extension of human narrative psychology. For the participants of the Iliad and its audiences, certain references are available only to what has already happened. Events posterior to the story being told, even when known, are obscured and refracted.

This digression helps us think in part about the way book 11 engages with narrative traditions. Frequently, when I read the Iliad with people for the first time, they express surprise that the poem has neither the death of Achilles nor the trick of the wooden horse. The Iliad strains at logic to refer to Achilles’ death many times without actually showing it: From Thetis’ mention in book 1, Achilles’ own in book 9, to echoes of Achilles’ death through Patroklos’, the epic provides ample evidence that Achilles’ death at the hands of Paris and Apollo was well known (and predicted by Hektor!) But while the scene itself must be left aside, the Iliad can’t resist toying with it in the wounding of Diomedes in book 11.

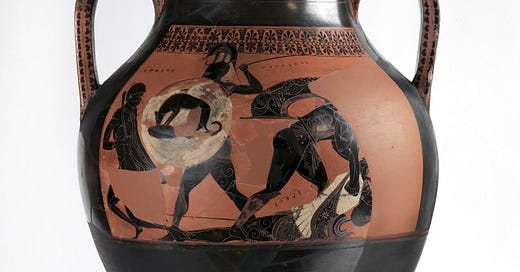

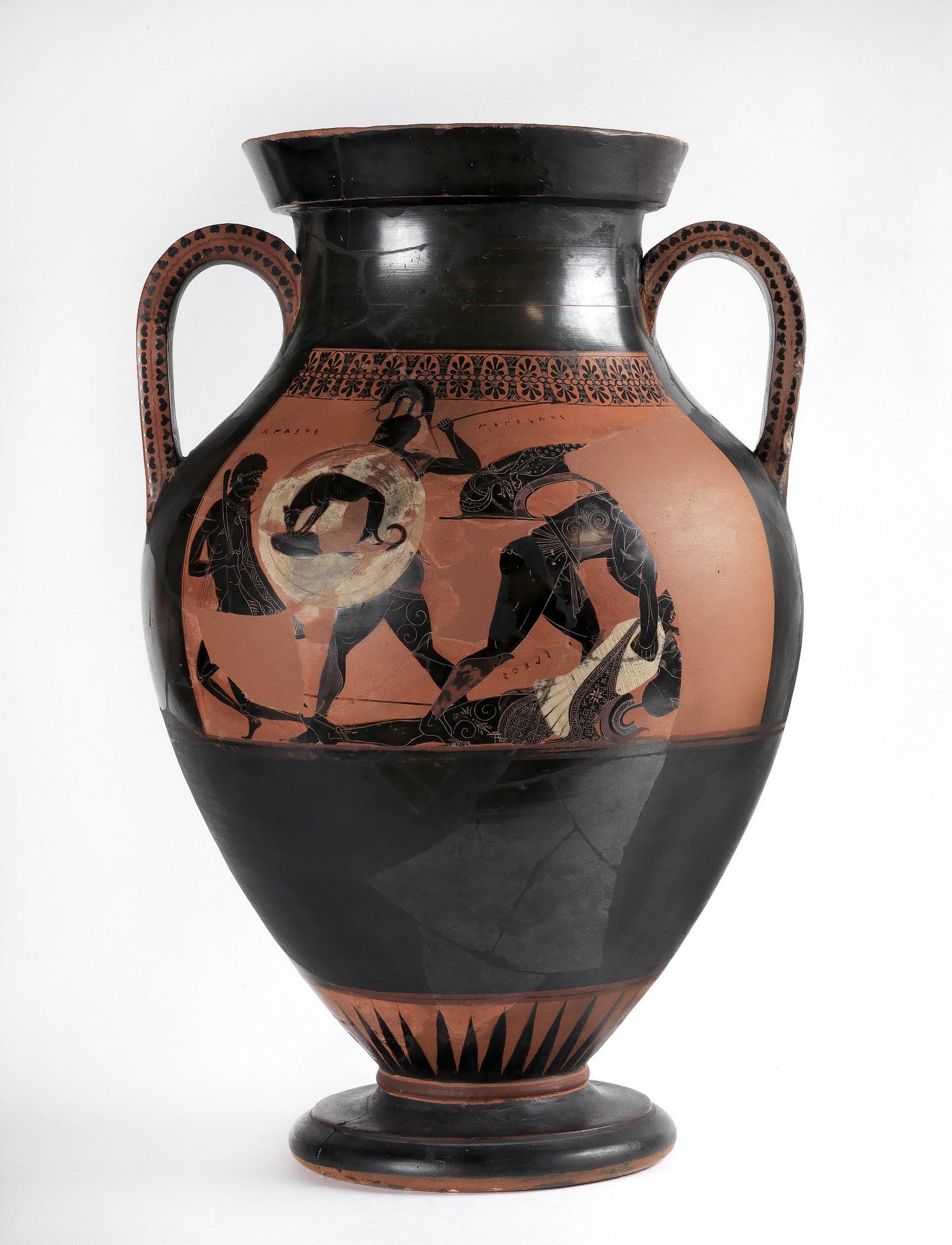

It is fairly well established in Homeric scholarship that Diomedes functions as a “replacement Achilles” from books 2 through 15 (see Von der Mühll 1952, 195-6; Lohmann 1970, 251; Nagy 1979, 30-1; Griffin 1980, 74; and Schofield 1999, 29 for a recent bibliography). In Iliad 11, after Paris wounds Diomedes in the right foot, he boasts and Diomedes flips out, before departing the battlefield. This curious scene has served has been seen as echoing the death of Achilles in the Aithiopis (based on Paris’ agency, the wound location and the substitution of Diomedes for Achilles elsewhere in the Iliad: see cf. Kakridis 1949, 85-8; Kakridis 1961, 293 n.1; and Burgess 2009, 74-5.)

Homer, Il. 11. 368-83

Then Alexander, the husband of well-coiffed Helen,

stretched his bow at Tydeus’ son, the shepherd of the host,

as he leaned on the stele on the man-made mound

of Ilus the son of Dardanios, the ancient ruler of the people.

While [Diomedes] took the breastplate of strong Agastrophes

from his chest and the shining shield from his shoulders

along with the strong helmet. Paris drew back the length of his bow

and shot: a fruitless shot did not leave his hand,

he hit the flat of his right foot, and the arrow stuck straight through

into the earth. Paris laughed so very sweetly

as he left his hiding place and spoke in boast:

“You’re hit! The shot did not fly in vain! I wish that

I hit you near the small of you back and killed you:

that way the Trojans would retreat from their cowardice,

those men who scatter before you like she-goats before a lion!”αὐτὰρ ᾿Αλέξανδρος ῾Ελένης πόσις ἠϋκόμοιο

Τυδεΐδῃ ἔπι τόξα τιταίνετο ποιμένι λαῶν,

στήλῃ κεκλιμένος ἀνδροκμήτῳ ἐπὶ τύμβῳ

῎Ιλου Δαρδανίδαο, παλαιοῦ δημογέροντος.

ἤτοι ὃ μὲν θώρηκα ᾿Αγαστρόφου ἰφθίμοιο

αἴνυτ’ ἀπὸ στήθεσφι παναίολον ἀσπίδα τ’ ὤμων

καὶ κόρυθα βριαρήν· ὃ δὲ τόξου πῆχυν ἄνελκε

καὶ βάλεν, οὐδ’ ἄρα μιν ἅλιον βέλος ἔκφυγε χειρός,

ταρσὸν δεξιτεροῖο ποδός· διὰ δ’ ἀμπερὲς ἰὸς

ἐν γαίῃ κατέπηκτο· ὃ δὲ μάλα ἡδὺ γελάσσας

ἐκ λόχου ἀμπήδησε καὶ εὐχόμενος ἔπος ηὔδα·

βέβληαι οὐδ’ ἅλιον βέλος ἔκφυγεν· ὡς ὄφελόν τοι

νείατον ἐς κενεῶνα βαλὼν ἐκ θυμὸν ἑλέσθαι.

οὕτω κεν καὶ Τρῶες ἀνέπνευσαν κακότητος,

οἵ τέ σε πεφρίκασι λέονθ’ ὡς μηκάδες αἶγες.

I think this speech indicates in part a Homeric dismissiveness against the death of Achilles in the tradition, as I argue in a paper from around a decade ago. Paris tries to boast wishes that Diomedes were actually killed. This is not a standard battlefield taunt; even as Paris celebrates a the wound everyone in the audience knows is fatal for others, he asserts that it is not so now. The nervous laughter and admission of Trojan cowardice highlights the awkwardness of this scene and its lack of verisimilitude.

Diomedes’ response supports this, to an extent

Homer, Il. 11.384-400

Unafraid, strong Diomedes answered him:

“Bowman, slanderer shining with your horn, girl-watcher—

if you were to be tried in force with weapons,

your strength and your numerous arrows would be useless.

But now you boast like this when you have scratched the flat of my foot.

I don’t care, as if a woman or witless child had struck me—

for the shot of a cowardly man of no repute is blunt.

Altogether different is my sharp shot:

even if barely hits it makes a man dead fast;

then the cheeks of his wife are streaked with tears

and his children orphans. He dyes the earth red with blood

and there are more birds around him than women.”So he spoke, and spear-famed Odysseus came near him

and stood in front of him. As he sat behind him, he drew the sharp shaft

from his foot and a grievous pain came over his skin.

He stepped into the chariot car and ordered the charioteer

to drive to the hollow ships since he was vexed in his heart.Τὸν δ’ οὐ ταρβήσας προσέφη κρατερὸς Διομήδης·

τοξότα λωβητὴρ κέρᾳ ἀγλαὲ παρθενοπῖπα

εἰ μὲν δὴ ἀντίβιον σὺν τεύχεσι πειρηθείης,

οὐκ ἄν τοι χραίσμῃσι βιὸς καὶ ταρφέες ἰοί·

νῦν δέ μ’ ἐπιγράψας ταρσὸν ποδὸς εὔχεαι αὔτως.

οὐκ ἀλέγω, ὡς εἴ με γυνὴ βάλοι ἢ πάϊς ἄφρων·

κωφὸν γὰρ βέλος ἀνδρὸς ἀνάλκιδος οὐτιδανοῖο.

ἦ τ’ ἄλλως ὑπ’ ἐμεῖο, καὶ εἴ κ’ ὀλίγον περ ἐπαύρῃ,

ὀξὺ βέλος πέλεται, καὶ ἀκήριον αἶψα τίθησι.

τοῦ δὲ γυναικὸς μέν τ’ ἀμφίδρυφοί εἰσι παρειαί,

παῖδες δ’ ὀρφανικοί· ὃ δέ θ’ αἵματι γαῖαν ἐρεύθων

πύθεται, οἰωνοὶ δὲ περὶ πλέες ἠὲ γυναῖκες.

῝Ως φάτο, τοῦ δ’ ᾿Οδυσεὺς δουρικλυτὸς ἐγγύθεν ἐλθὼν

ἔστη πρόσθ’· ὃ δ’ ὄπισθε καθεζόμενος βέλος ὠκὺ

ἐκ πόδος ἕλκ’, ὀδύνη δὲ διὰ χροὸς ἦλθ’ ἀλεγεινή.

ἐς δίφρον δ’ ἀνόρουσε, καὶ ἡνιόχῳ ἐπέτελλε

νηυσὶν ἔπι γλαφυρῇσιν ἐλαυνέμεν· ἤχθετο γὰρ κῆρ.

There’s a lot going on in this speech! It simultaneously attempts to minimize Paris’ accomplishment (as minor, as emasculating, etc.) and allows Diomedes to vaunt about his own martial prowess while also acknowledging that the foot wound is still serious enough to sideline Diomedes from battle. Perhaps part of the point is to ridicule Paris and emphasize that Achilles’ future death has more to do with fate and Apollo; on the other hand, I think it can equally position the Iliad as engaging critically with the tradition of the Trojan War. Given the scale of violence in this epic and the brutal loss of life throughout, a foot wound taking out the most powerful warrior may seem absurd. Indeed, in this epic, Achilles takes himself out of the battle. Yet, even given potential mockery, I have to concede that the allusion to Achilles’ death might also acknowledge how the most powerful forces can be undone by surprisingly minor things.

The meaning of Diomedes’ foot wound, however, shifts based on what audiences know and how they are reacting to the story in play. Some might take the familiar details as comforting, as invoking an ending they know well; for others, it may be a moment of consternation, playing on that tension between ‘Homeric realism’ and the fantasy of broader myth.

Reading Questions for Book 11

How are the interventions of the gods different in this book from books 9 and 10? Why?

How do the events of the book shape the characterization of the characters? Pay special attention to speeches from Agamemnon and Diomedes?

What is Nestor’s speech to Patroklos like and how does it influence his action?

A short bibliography on Diomedes and book 11

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Andersen, Öivind. 1978. Die Diomedesgestalt in der Ilias. Oslo.

Barker, E. T.E. and Christensen, Joel P. 2008. “Oidipous of Many Pains: Strategies of Contest in the Homeric Poems.” LICS 7.2. http://www.leeds.ac.uk/classics/lics/).

Burgess, Jonathan. 2001. The Tradition of the Trojan War in Homer and the Epic Cycle. Baltimore.

—,—. 2009. The Death and Afterlife of Achilles. Baltimore.

Christensen, Joel P. 2009. “The End of Speeches and a Speech’s End: Nestor, Diomedes, and the telos muthôn.” in Kostas Myrsiades (ed.). Reading Homer: Film and Text. Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 136-62.

Christensen, Joel P. and Barker, Elton T. E.. “On not remembering Tydeus: Agamemnon, Diomedes and the contest for Thebes.” Materiali e Discussioni per l’Analisi dei Testi Classici, no. 66, 2011, pp. 9-44.

Christensen, Joel P. 2015. “Diomedes’ Foot-wound and the Homeric Reception of Myth.” In Diachrony, Jose Gonzalez (ed.). De Gruyter series, MythosEikonPoesis. 2015, 17–41.

Dunkle, Roger. 1997. “Swift-Footed Achilles.” CW 90: 227-34

Gantz, Timothy. 1993. Early Greek Myth. Baltimore.

Griffin, Jasper. 1980. Homer on Life and Death. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

—,—.2001. “The Epic Cycle and the Uniqueness of Homer.” in Cairns 2001: 363-84.

Irby-Massie. Georgia. 2009. “The Art of Medicine and the Lowly Foot: Treating Aches, Sprains, and Fractures in the Ancient World.” Amphora 8: 12-15.

Irene J. F. de Jong. “Convention versus Realism in the Homeric Epics.” Mnemosyne 58, no. 1 (2005): 1–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4433613.

Kakridis, Johannes Th. 1949. Homeric Researches. Lund.

Kakridis, Phanis, J. 1961. “Achilles’ Rüstung.” Hermes 89: 288-97.

Lohmann, Dieter. 1970. Dieter Lohmann. Die Komposition der Reden in der Ilias. Berlin.

Morris, I. and Powell, B., eds. 1997. A New Companion to Homer. Leiden.

Mühll, Peter von der. 1952. Kritisches Hypomena zur Ilias. Basel.

Nagy, Gregory. 1979. The Best of the Achaeans. Baltimore.

Nickel, Roberto. 2002. “Euphorbus and the Death of Achilles.” Phoenix 56: 215-33.

Pache, Corinne. 2009. “The Hero Beyond Himself: Heroic Death in Ancient Greek Poetry and Art.” in Sabine Albersmeir (ed.). Heroes: Mortals and Myths in ancient Greece. Baltimore (Walters Art Museum): 89-107.

Redfield, James. 1994. Nature and Culture in the Iliad: The Tragedy of Hektor. Chicago.

Schofield, M.1999. Saving the City: Philosopher Kings and Other Classical Paradigms. London.

Vernant, J.-P. 1982. “From Oidipous to Periander: Lameness, Tyranny, Incest, in Legend and History.” Arethusa 15: 19-37.

—,—. 2001. “A ‘Beautiful Death’ and the Disfigured Corpse.” in Cairns 2001: 311-41.

Willcock, M. 1977. 1977. “Ad hoc invention in the Iliad.” HSCP 81: 41-53.