This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 12. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Iliad 12 tells the story of the battle around the walls that protect the Achaean ships. Like other books of the Iliad, remarkable speeches intersperse the action. One of the most famous Homeric speeches appears about two-thirds of the way through the book as the Trojan ally, Sarpedon—a son of Zeus—turns to speak to his friend Glaukos:

Homer, Iliad 12.310-328

‘Glaukos, why are you and I honored before others

by place, the best meat and cups filled with wine

in Lykia, and all men look on us as gods,

and we have great tracts of land Xanthos’ banks,

good holdings with orchards and vineyards, farmland for wheat too?

Because of this we must stand at the head of the Lykians

and take our part of the burden of battle’s fire

so that one of those well-armored Lykians may see us and say:

“Indeed, these lords of Lykia are no base-born men,

these kings of ours, who dine on the fatted sheep selected for them

and drink the finest wine, since there is in fact strength

and courage in them, when they fight in the forefront of the Lykians.”But, friend, imagine if you and I could escape this battle

and be able to live forever, ageless, immortal–

then neither would I myself go on fighting in the frontlines

nor would I tell you to seek the fighting that brings us glory.

But now, since death’s ghosts stand around us numbered

in their thousands and no person can ever escape them,

let’s go on and claim this glory for ourselves or give it to others in turn.”Γλαῦκε τί ἢ δὴ νῶϊ τετιμήμεσθα μάλιστα

ἕδρῃ τε κρέασίν τε ἰδὲ πλείοις δεπάεσσιν

ἐν Λυκίῃ, πάντες δὲ θεοὺς ὣς εἰσορόωσι,

καὶ τέμενος νεμόμεσθα μέγα Ξάνθοιο παρ’ ὄχθας

καλὸν φυταλιῆς καὶ ἀρούρης πυροφόροιο;

τὼ νῦν χρὴ Λυκίοισι μέτα πρώτοισιν ἐόντας

ἑστάμεν ἠδὲ μάχης καυστείρης ἀντιβολῆσαι,

ὄφρά τις ὧδ’ εἴπῃ Λυκίων πύκα θωρηκτάων·

οὐ μὰν ἀκλεέες Λυκίην κάτα κοιρανέουσιν

ἡμέτεροι βασιλῆες, ἔδουσί τε πίονα μῆλα

οἶνόν τ’ ἔξαιτον μελιηδέα· ἀλλ’ ἄρα καὶ ἲς

ἐσθλή, ἐπεὶ Λυκίοισι μέτα πρώτοισι μάχονται.

ὦ πέπον εἰ μὲν γὰρ πόλεμον περὶ τόνδε φυγόντε

αἰεὶ δὴ μέλλοιμεν ἀγήρω τ’ ἀθανάτω τε

ἔσσεσθ’, οὔτέ κεν αὐτὸς ἐνὶ πρώτοισι μαχοίμην

οὔτέ κε σὲ στέλλοιμι μάχην ἐς κυδιάνειραν·

νῦν δ’ ἔμπης γὰρ κῆρες ἐφεστᾶσιν θανάτοιο

μυρίαι, ἃς οὐκ ἔστι φυγεῖν βροτὸν οὐδ’ ὑπαλύξαι,

ἴομεν ἠέ τῳ εὖχος ὀρέξομεν ἠέ τις ἡμῖν.

In this speech Sarpedon first rhetorically affirms their privileged position among their countrymen and then asserts that it is this very position that obligates them to prove their noble worth through noble deeds—deeds that will earn them fame. The two men, according to Sarpedon, are honored like immortals and that they are treated as immortals requires them to attain the immortality that is available for men (that is, kleos).

The near divine honors that they receive, the very acts that require them to seek kleos, are material (food, wine, land). Following this statement, Sarpedon wishes that they were immortal so they would not have to fight, touching upon the irony of heroic immortality, an immortality that is something completely different from that of the Olympian gods. Since they are mortal and they will die no matter what, they should go into battle and “win glory or give it to someone else.”

It is life’s status as a limited commodity that gives those who risk it a share of the immortal in the form of fame. In discussing Homeric heroism, Margalit Finkelberg refers to Sarpedon’s speech writes “The Iliad proceeds from an idea of hero' which is pure and simple: one who prizes honour and glory above life itself and dies on the battlefield in the prime of life” (1995, 1). Adam Parry cites this passage when he asserts that “moral standards as values of life are essentially agreed on by everyone in the Iliad” (1956, 3; see Pucci 1998, 49-68 for an extended discussion of this passage). And many other authors (see Hammer 2002, Adkins 1982) agree with this. But I think the key phrase in Finkelberg’s sentence is proceeds from. The epic does not by any means insist that this articulation of values is unquestionable or, ultimately, good. As James Arieti suggests (1986, 1), the basic framework of these values are assumed in book 1, where Hera has Athena promise Achilles that he will be compensated 3 or 4 times over for his loss of honor (1.213) but ultimately questioned in book 9 by Achilles dissent.

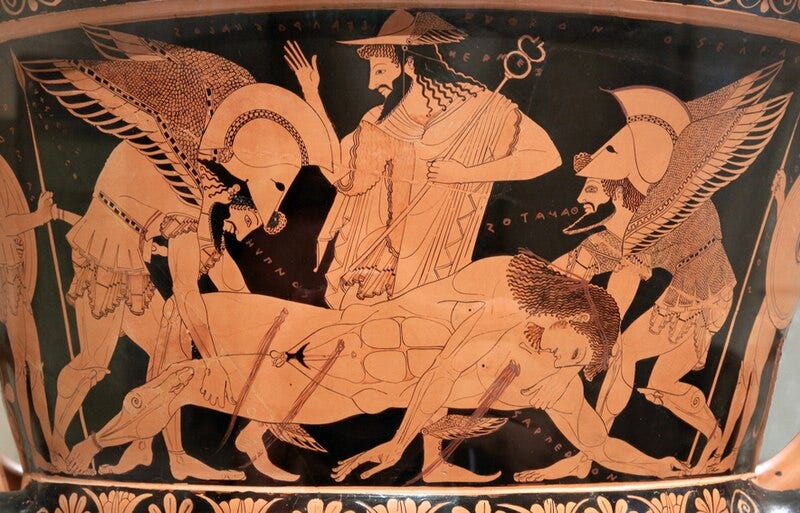

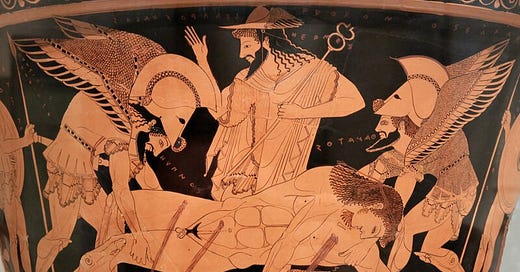

To fully understand Sarpedon’s comments, they need to be contextualized in the action of book 12 and the flow of the plot since the embassy to Achilles. Achilles’ rejection of the offer of the gifts stands in contrast to his commitment to stay and fight, regardless of what he will receive. Book 12 is the first significant commentary on heroic behavior since the embassy, and the actions center around the Achaean chieftains who have no choice but to defend the walls around the ships and Hektor as he tries to break through the wall. As S. Faron argues, Sarpedon is the one who does the most in battle in this book and, by contrast, Hektor’s grasping for glory might seem more desperate or ill-considered. Yet, even if Sarpedon’s comments ring noble, they are attenuated by his eventual death, one so prominent that it prompts Zeus to cry tears of blood.

I have no doubt that Sarpedon presents something of a standard heroic ‘code’ in this passage. The question, as usual, is to what extent we are supposed to accept the standard articulation as sufficient or still applying. A key note of dissonance here is the contrast between Sarpedon’s dream of immortality and Hektor’s boast in book 8. There Hektor says,

Tomorrow will show the proof of our excellence, if he will stand

To face my spear’s approach. But I think that he will fall there

Struck among the first ranks and many of his companions

Will be there around him as the sun sets toward the next dear.

But I wish I were deathless and ageless for all time,

Then I would pay them back as Athena or Apollo might,

And now on this day bring evil to the Argives.

So Hektor spoke and the Trojans cheered in response.

One significant contrast between this wish and Sarpedon’s is the audience: Sarpedon speaks only to Glaukos as they face death in an intimate way, acknowledging that, just maybe, facing men with spears on top of a wall is a less desirable way to spend a life than dining and drinking. Hektor, in contrast, speaks in bluster to rally his troops to do something they have never done before (remain outside the walls and face the Achaeans.

I find it interesting that there is some contrast in the scholiastic response to this. Hektor’s wish to be immortal is denigrated (“Praying for the impossible is barbaric” βαρβαρικὸν τὸ εὔχεσθαι τὰ ἀδύνατα, Schol. bT ad Hom. Il. 8.538-539b) while Sarpedon’s reverie is praise as “a noble sentiment” (εὐγενὴς ἡ γνώμη, Schol. b ad Hom. Il. 12.322-8 ex.). Sarpedon’s odd detachment seems somehow more to the taste of Hektor’s more desperate energy.

And this gets me to the primary differences in the statements and the core of what I see as the Iliad’s stance on this kind of heroism. Achilles can linger by his ships, indulging in navel-gazing and worrying about life’s meaning, because no one is forcing him to fight. They are asking him. Similarly, Sarpedon–also a demi-god–comes as an ally who fights for the promise of honor, goods, and glory. Hektor knows what Achilles only learns too late: if he does not fight, everyone he loves dies. All the words of honor and glory and any sense of noblesse oblige ring hollow in comparison to this. And I think that any reading of Sarpedon’s speech that does not acknowledge audience familiarity with his death misses a crucial aspect of its interpretation.

Sarpedon’s articulation, I think, has drawn praise over the ages because it isn’t messy. He doesn’t talk about not fighting; he idly imagines a life of ease and makes the choice to stand. Hektor’s prevarication and later vacillation in the face of danger troubles us because however fantastic it may sound, it is not a fantasy. His fight is about survival; any talk of glory is just a distraction from the mortal truth.

And there’s a moral content as well. What does it mean for audiences to praise the exploits of ‘heroes’ who fight for personal gain and intangible, indefinable, things like fame? Achilles doubts this; Sarpedon merely restates this; the rest of the epic helps us judge the matter for ourselves.

Short bibliography on Sarpedon’s Speech

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Adkins, A. W. H. “Values, Goals, and Emotions in the Iliad.” Classical Philology 77, no. 4 (1982): 292–326. http://www.jstor.org/stable/269413.

Arieti, James A. “Achilles’ Alienation in ‘Iliad 9.’” The Classical Journal 82, no. 1 (1986): 1–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3297803.

Farron, S. “THE CHARACTER OF HECTOR IN THE ‘ILIAD.’” Acta Classica 21 (1978): 39–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24591547.

Finkelberg, Margalit. “Odysseus and the Genus ‘Hero.’” Greece & Rome 42, no. 1 (1995): 1–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/643068.

HAMMER, DEAN. “THE ‘ILIAD’ AS ETHICAL THINKING: POLITICS, PITY, AND THE OPERATION OF ESTEEM.” Arethusa 35, no. 2 (2002): 203–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44578882.

Howald, Ernst. “Sarpedon.” Museum Helveticum 8, no. 2/3 (1951): 111–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24811891.

A. Parry, 1956. “The Language of Achilles,” TAPA 87, 1-8.

P. Pucci,1998. The Song of the Sirens: Essays on Homer, Lanham.

Bonus Sarpedon Content

Pindar, Pythian 3.108-116

“I’ll be small for minor matters but big for big ones

and I will cultivate in my thoughts

The fate that comes to me, serving it by my own design.So if god allows me wealth’s luxury

I have hope of finding fame’s height as well.We know about Nestor and Lykian Sarpedon–

People’s legends, from famous songs which

The wise craftsmen assembled. And excellence blooms

In famous songs for all time. But it is easy for only a few to earn.”σμικρὸς ἐν σμικροῖς, μέγας ἐν μεγάλοις

ἔσσομαι, τὸν δ᾿ ἀμφέποντ᾿ αἰεὶ φρασίν

δαίμον᾿ ἀσκήσω κατ᾿ ἐμὰν θεραπεύων μαχανάν.

εἰ δέ μοι πλοῦτον θεὸς ἁβρὸν ὀρέξαι,

ἐλπίδ᾿ ἔχω κλέος εὑρέσθαι κεν ὑψηλὸν πρόσω.

Νέστορα καὶ Λύκιον Σαρπηδόν᾿, ἀνθρώπων φάτις,

ἐξ ἐπέων κελαδεννῶν, τέκτονες οἷα σοφοί

ἅρμοσαν, γινώσκομεν· ἁ δ᾿ ἀρετὰ κλειναῖς ἀοιδαῖς

χρονία τελέθει· παύροις δὲ πράξασθ᾿ εὐμαρές.

What this series is bringing home to me is how transactional the Iliad is. We start with buying off Apollo and finish with Priam buying back Hector's corpse. The one deal you can't make, says Achilles in book 9 (and Sarpedon here) is buying a man back from death.

I think there is a contrast between the weirdly specific and weirdly symmetrical deals in book 10 (info on whether the ships are guarded: horses and chariot, info on whether they have retreated to Troy: black sheep) and the contract outlined by Sarpedon. The book 10 deals are enforceable promises, Sarpedon is king anyway but is explaining the social contract by which he gets to stay king. Fighting earns him his meals and his temenos and also the assent of the Lycians to him having those things. Book 10 is contract law, Sarpedon is reprocity.

wow thank you for this