This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 21. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 21 of the Iliad is like one of those extended fight scenes in a Transformers or Marvel movie: superpowered giants smashing against one another in a dizzying array of violence that leaves almost any audience reeling with confusion, immersed in a battlefield but uncertain how things are going. The effect can be to lose the thread of the narrative, to sit with the action itself and feel wearied, bewildered. An adventurous modernist reading might suggest that this is the very point, to bring the fog of war to an audience reclining on their couches or seated near friends.

The Iliad (and those CGI-filled modern movies) is doing more than this, however. The violence itself is somewhat formulaic, alluding to other fight scenes, to other narrative traditions that help us understand the one we are witnessing. And the mayhem sets up new emphasis in performance for when the bloodletting pauses: brief exchanges in the eye of the battlefield’s storm are charged. In Iliad 21 there are two moments that always stick out for me: the exchange between Achilles and Lykaon near the beginning of the book and the even briefer conversation between Poseidon and Apollo near its end. Both reflect on the brevity of human life; both engage with the Iliad’s narrative arc on mortality, violence, and heroism’s brittle promises.

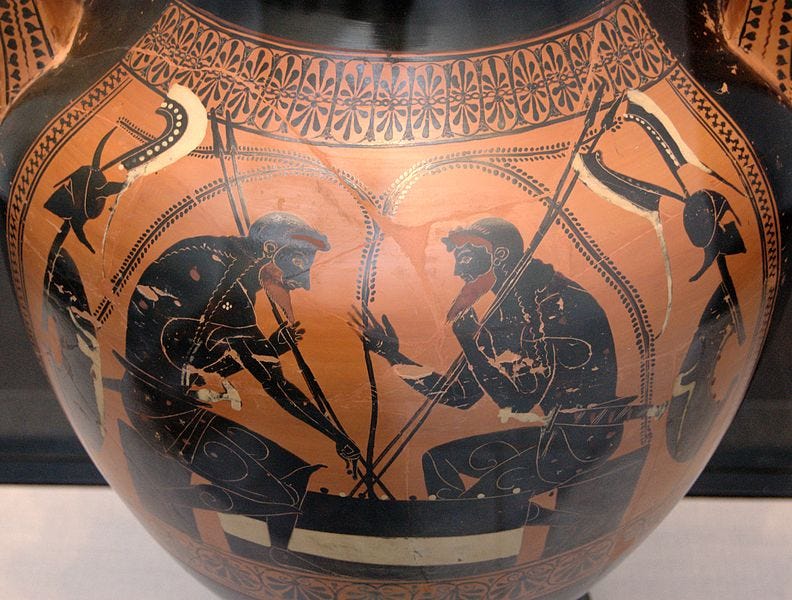

After Achilles has captured and passed on twelve Trojan youths to slaughter over Patroklos’ funeral pyre, he encounters the son of Priam, Lykaon, whom we learn he had captured earlier in the war and ransomed back to his family. When Lykaon sees Achilles, he rushes to him to grab his knees “and he was deeply desiring in his heart / to flee terrible death and dark fate” (περὶ δ' ἤθελε θυμῷ ἐκφυγέειν θάνατόν τε κακὸν καὶ κῆρα μέλαιναν, 21.65-66). Achilles pushes him back and gives one of the most memorable speeches from the Iliad.

Iliad 21.103-10

“So the glorious son of Priam addressed him,

Begging with words, but he heard a cruel voice

‘Fool, don’t mention ransom to me nor address me in public.

Before the fateful day took Patroklos away

Then is was dearer to my thoughts to spare Trojans,

And I took many of them alive and then sold them back.

But now there is no one who will avoid death, no one

whom the god, at least, puts in my hands in front of Troy,

no one of all the Trojans, and especially the sons of Priam.

So friend, die too. Why do you mourn like this?

Even Patroklos died and he was much better than you.

Do you not see what kind of man I am, how fine and large?

I come from a noble father and a divine mother bore me,

but strong fate and death await me too.

There will come a time at dawn, in the afternoon, or at midday

When some Ares rips the life from even me

Either by striking me with a spear or from a bowstring.”῝Ως ἄρα μιν Πριάμοιο προσηύδα φαίδιμος υἱὸς

λισσόμενος ἐπέεσσιν, ἀμείλικτον δ’ ὄπ’ ἄκουσε·

νήπιε μή μοι ἄποινα πιφαύσκεο μηδ’ ἀγόρευε·

πρὶν μὲν γὰρ Πάτροκλον ἐπισπεῖν αἴσιμον ἦμαρ

τόφρά τί μοι πεφιδέσθαι ἐνὶ φρεσὶ φίλτερον ἦεν

Τρώων, καὶ πολλοὺς ζωοὺς ἕλον ἠδ’ ἐπέρασσα·

νῦν δ’ οὐκ ἔσθ’ ὅς τις θάνατον φύγῃ ὅν κε θεός γε

᾿Ιλίου προπάροιθεν ἐμῇς ἐν χερσὶ βάλῃσι

καὶ πάντων Τρώων, περὶ δ’ αὖ Πριάμοιό γε παίδων.

ἀλλὰ φίλος θάνε καὶ σύ· τί ἦ ὀλοφύρεαι οὕτως;

κάτθανε καὶ Πάτροκλος, ὅ περ σέο πολλὸν ἀμείνων.

οὐχ ὁράᾳς οἷος καὶ ἐγὼ καλός τε μέγας τε;

πατρὸς δ’ εἴμ’ ἀγαθοῖο, θεὰ δέ με γείνατο μήτηρ·

ἀλλ’ ἔπι τοι καὶ ἐμοὶ θάνατος καὶ μοῖρα κραταιή·

ἔσσεται ἢ ἠὼς ἢ δείλη ἢ μέσον ἦμαρ

ὁππότε τις καὶ ἐμεῖο ῎Αρῃ ἐκ θυμὸν ἕληται

ἢ ὅ γε δουρὶ βαλὼν ἢ ἀπὸ νευρῆφιν ὀϊστῷ.

῝Ως φάτο, τοῦ δ’ αὐτοῦ λύτο γούνατα καὶ φίλον ἦτορ·

This scene should remind readers of discussion between Agamemnon and Menelaos in book 6 when the former tells his brother not to spare a suppliant Trojan. That moment follows the theomachy-resonant chaos of book 5 and extends the transgression against reciprocity in the ransom denied in book 1 (when Agamemnon refuses to give Chryseis back) to the battlefield. The Iliad’s war has no rules or boundaries and the sequence in book 21, starting with the ransom-denied followed by a second (or third or fourth?) theomachy creates a reminder and a narrative ring. All of the tension of battle, all of the extremity of war is loaded into Achilles’ fury.

This speech is marked out as different, moreover, before it even begins. To my knowledge, this is one of the only examples in Greek epic of a speech introduction that emphasizes the recipient’s position rather than the speaker. The transition “begging with words, but he heard a cruel voice” makes Achilles somewhat more distance from the external audience (us) and may have the effect of drawing our perspective closer to Lykaon’s than Achilles.

If we were to cluster together a few of Achilles’ speeches after the death of Patroklos, it would be easy to see how much he continues the motif of surrogacy, mourning over the fact that Patroklos took his place in war when he imagined instead that Patroklos would take his own place in life when he was gone. Patroklos has become for Achilles a “transitional object”, through him he is seeing himself and others differently. Many readers have made thematic connections between this plot and the story of the Gilgamesh poems, where it is through the death and loss of Enkidu that the god-king of Uruk realizes his own mortality, transitioning his narrative from one of adventure to a journey for eternal life.

I am agnostic about any literal connection between the Gilgamesh poems and Homer (I think we make the connections and have no idea if ancient audiences could have). But I think there is also a significant difference between the two situations. Losing Patroklos does not make Achilles value his life more or desire to extend it. Instead, it induces in him a murderous nihilism: first, he laments that he didn’t die instead (rather than mourning for the portion of life denied to his friend), then becomes an instrument of death himself (instead of a vessel seeking for more life). (At least I put it somewhat this way when I wrote among some other of my juvenalia “Achilles internalises and then generalises Patroklos’ death: these two passages reveal his acceptance of his own death but here he goes further. In denying the obligations of suppliancy, he himself becomes the instrument of death’s inevitability” (2009, 191)

Achilles’ “identification” with Patroklos through death emerges as a kind of jejune narcissism, a philosophizing or catastrophizing adolescent first imagining that the universe ceases to be with his own death and then in some way seeking to make it happen. Note the rapid movement in that second part from Lykaon, to Patroklos, to Achilles himself. If I am right that there is a thematic movement in Achilles’ grief that helps him see others as real again, then this speech should be seen as a negative turn from his lament in book 19. He acknowledges Lykaon as another person, but considers him less than himself and insofar as people he loved have died, everyone is due to die too.

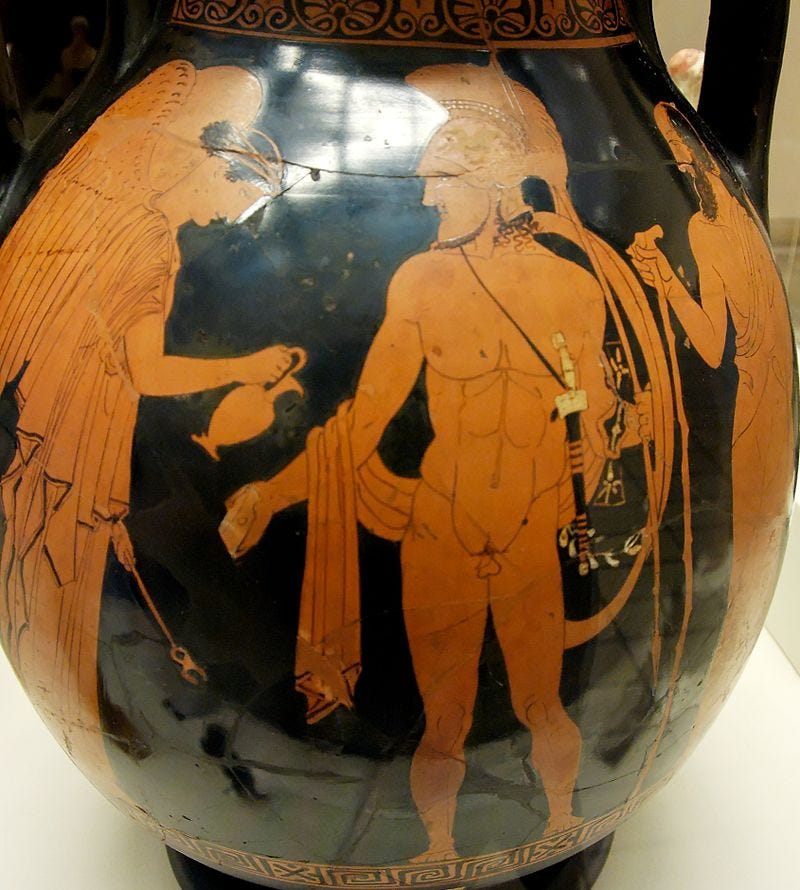

There’s a lot of interesting language in this section about beauty and the body. From the grasping at the knees to Achilles’ spearing of Lykaon after this speech where he points to his own body, the language here may flirt with the erotic as Achilles projects his loss—his lack of the rest of himself—on the world around him. In her recent book, Rachel Lesser suggests (following Vermeule 1979) “Here Achilleus’ spear metonymically, expresses the hero’s own frustrated desire, and its phallic shape suggests the similarity between aggressive and sexual urges” (2022, 206). Read in an intrageneric context of song—where lyric and elegy exist alongside epic and we understand Achilles as mourning his lost companion—this scene has a sense of displaced desire.

In addition to providing insight into the tension of desire that can never be fulfilled, Achilles’ language in this passage also speaks to the symbolism of the heroic body. As I discuss in an article on disability studies and Homeric epic “Homeric poetry presents a system in which to have a beautiful body signals an authoritative place in a community and a monstrous or disabled body de-authorizes or dehumanizes a figure” (2022). Frequently observations on body size and shape are used to confirm membership in a particular class. When Athena sees Telemachus in the Odyssey, she says “I see that you are really big and noble, and brave” μάλα γάρ σ’ ὁρόω καλόν τε μέγαν τε, 1.302: = 3.199 (Nestor addressing Telemachus). Cf. 4.141–47 where Helen recognizes Telemachus because he looks like his father and Menelaos responds “I was just now thinking this too, wife, as you note the similarity: / these are the kinds of feet and hands / the eye glances, and head and hair belonging to that man” (οὕτω νῦν καὶ ἐγὼ νοέω, γύναι, ὡς σὺ ἐΐσκεις· / κείνου γὰρ τοιοίδε πόδες τοιαίδε τε χεῖρες / ὀφθαλμῶν τε βολαὶ κεφαλή τ’ ἐφύπερθέ τε χαῖται, 4.148–50).

By using similar language, Achilles acknowledges the physiognomic assumptions of heroic bodies, but insists that they are still subject to the rules of mortality. In the broader context of heroic myth, Achilles is emphasizing that heroes do in fact die and that their perfect bodies are not proof against human decay and weakness. He articulates this for himself when he more or less correctly predicts his own death (“by a spear or an arrow”).

As a final note, the tone of Achilles’ opening address to Lykaon as “friend” has been read as biting or sarcastic. But if we reconsider the etymology of philos as indicating something that is part or akin to you, Achilles’ address to Lykaon may signal a transfer of identity or a sharing of class. When Achilles calls Lykaon “friend”, then, he performs a kind of identification that obscures the boundaries between the two of them and his lost companion.

Christensen, Joel P. 2009. “Universality or Priority? The Rhetoric of Death in the Gilgamesh Poems and the Iliad.” In Quaderni del Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Antichità e del Vicino Oriente dell’Università Ca’ Foscari, 4. E. Cingano and L. Milano (eds.), 179–202.

Christensen, Joel. P. 2021. “Beautiful Bodies, Beautiful Minds: Some Applications of Disability Studies to Homer.” Classical World 114.4: 365–393.

Danek, Georg. “Troilos und Lykaon : ein Beitrag zur Intertextualität Homers.” Geistes-, Sozial- und Kulturwissenschaftlicher Anzeiger, vol. 151, no. 1, 2016, pp. 5-54.

Fisher, Nick. “The friendships of Achilles and the killing of Lykaon.” Ethics in ancient Greek literature: aspects of ethical reasoning from Homer to Aristotle and beyond : studies in honour of Ioannis N. Perysinakis. Ed. Liatsi, Maria. Trends in Classics. Supplementary Volumes; 102. Berlin ; Boston (Mass.): De Gruyter, 2020. 31-57. Doi: 10.1515/9783110699616-003

Karp, Andrew. “The harmony of eleos and aidôs in the moral universe of the Iliad.” New England classical newsletter & journal, vol. 21, 1993-1994, pp. 106-110.

Lane, Nicholas. “Homer, Iliad 21.51-52.” Illinois Classical Studies, vol. 30, 2005, pp. 7-9.

Lesser, Rachel. 2022. Desire in the Iliad. Oxford.

MUELLNER, L. Metonymy, Metaphor, Patroklos, Achilles. Classica: Revista Brasileira de Estudos Clássicos, [s. l.], v. 32, n. 2, p. 139–155, 2019. DOI 10.24277/classica.v32i2.884