This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations. Don’t forget about Storylife: On Epic, Narrative, and Living Things. Here is its amazon page. here is the link to the company doing the audiobook and here is the press page. I am happy to talk about this book in person or over zoom.

Last year, I wrote seven posts about book 24. Certainly, there can’t be more to say?

The funeral games occupy the majority of Iliad 23, but the book begins with Achilles mourning the lost of Patroklos. At the end of the book, everyone else returns to sleep. Book 24 begins again with Achilles where he was at the beginning of 23: alone, at night, missing Patroklos:

Iliad 24.3-20

“…but Achilles

Was weeping while he recalled his dear companion, not even sleep,

That master of everything overtook him, but he turned here and there

Longing for Patroklos’ manliness and his spirit,

And all those things he endured with him and the pains they shared

In the wars of men and testing the troubling seas.He let loose a warm tear as he recalled all this–

First he was lying on his side, then again on his back

And other times on his stomach. Then he stood straight up

And went grieving along the shore of the sea. Dawn

Was not yet about to sneak her way over the salt and sands.

But Achilles the yoked his horses to his chariot

And bound Hektor to be dragged behind the car

And pulled him three times around the grave of Menoitios’ dead son.

He stopped again near his dwelling and let Hektor lie there

On his face, stretched out in the dust. Apollo was holding

All disgrace back from the man’s skin, because he pitied

Him, even though he was dead.”ὕπνου τε γλυκεροῦ ταρπήμεναι· αὐτὰρ ᾿Αχιλλεὺς

κλαῖε φίλου ἑτάρου μεμνημένος, οὐδέ μιν ὕπνος

¿ρει πανδαμάτωρ, ἀλλ’ ἐστρέφετ’ ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα

Πατρόκλου ποθέων ἀνδροτῆτά τε καὶ μένος ἠΰ,

ἠδ’ ὁπόσα τολύπευσε σὺν αὐτῷ καὶ πάθεν ἄλγεα

ἀνδρῶν τε πτολέμους ἀλεγεινά τε κύματα πείρων·

τῶν μιμνησκόμενος θαλερὸν κατὰ δάκρυον εἶβεν,

ἄλλοτ’ ἐπὶ πλευρὰς κατακείμενος, ἄλλοτε δ’ αὖτε

ὕπτιος, ἄλλοτε δὲ πρηνής· τοτὲ δ’ ὀρθὸς ἀναστὰς

δινεύεσκ’ ἀλύων παρὰ θῖν’ ἁλός· οὐδέ μιν ἠὼς

φαινομένη λήθεσκεν ὑπεὶρ ἅλα τ’ ἠϊόνας τε.

ἀλλ’ ὅ γ’ ἐπεὶ ζεύξειεν ὑφ’ ἅρμασιν ὠκέας ἵππους,

῞Εκτορα δ’ ἕλκεσθαι δησάσκετο δίφρου ὄπισθεν,

τρὶς δ’ ἐρύσας περὶ σῆμα Μενοιτιάδαο θανόντος

αὖτις ἐνὶ κλισίῃ παυέσκετο, τὸν δέ τ’ ἔασκεν

ἐν κόνι ἐκτανύσας προπρηνέα· τοῖο δ’ ᾿Απόλλων

πᾶσαν ἀεικείην ἄπεχε χροῒ φῶτ’ ἐλεαίρων

καὶ τεθνηότα περ….

There are many things I find striking about this passage. Structurally, in the arc of the epic as a whole, it takes us back to book 1 where Apollo appears early as a guarantor of some kind of divine justice. In book 1, Apollo is summoned by Chryses to punish transgression against the reciprocal rite of supplication and ransom exchange. This open transgression is resolved when Achilles accepts Priam’s ransom of Hektor’s body. Within this meta-structural ring another theme is established as well: the right of all mortals to burial, supported in part by the truce in book 7 and Hera’s comments in book 16 that funeral rites are the geras thanontôn (“the honor-prize of the dead”).

Apollo serves a complementary but different role at the end of the epic: he appears again as an upholder of divine justice. This time, instead of punishing a transgression, he advocates for Hektor’s burial in a council of the gods that may anticipate or echo his juridical appearance in the story of the Oresteia (where he argues on Orestes’ behalf against the Furies). At the beginning and end of the epic, moreover, Apollo establishes the closest thing archaic poetry has on offer for a universal bill of human rights: the honoring of a suppliant and the burial of the dead. Note for modern comparison how children and parents are central in both instances.

A second thing to note about this passage is that ancient scholars marked some of the lines as spurious. The complaints fall into two broad categories: these lines are two simple or unpoetic; or they are in some way morally questionable.

Schol. A. ad Il. 24. 6-9 ex.

‘These four lines are considered suspect because they are simple and Achilles’ grief is more emphatic than it is depicted here [in lines 4-5]. People also complain that manliness and menos aren’t different at all. The poet rarely says manliness when he means braveness. It is also somewhat twisted up, when he ends with “remembering these things” when they already had “thinking of his companion” above.

Ariston. | Did. Πατρόκλου ποθέων (6) ἕως <τοῦ> τῶν μιμνησκόμενος (9): ἀθετοῦνται στίχοι τέσσαρες, ὅτι εὐτελεῖς εἰσιν, ἀρθέντων δὲ αὐτῶν καὶ ἐμφαντικώτερον δηλοῦται ἡ τοῦ ᾿Αχιλλέως λύπη· „ἀλλ' ἐστρέφετ' ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα” (Ω 5), „ἄλλοτ' ἐπὶ πλευράς” (Ω 10). καὶ τοῖς αὐτοῖς καταχρᾶται, ἀνδροτῆτα, μένος (6)· οὐδὲν γὰρ διαφέρει. καὶ οὐδέποτε ἀνδροτῆτα (6) εἴρηκε τὴν ἀνδρείαν, ἀλλ' ἠνορέαν. ἔχει δὲ καί τι δυσεξέλικτον, τῶν μιμνησκόμενος (9)· καὶ γὰρ ἄνω εἴρηκεν „ἑτάρου μεμνημένος” (Ω 4).

Schol. bT. ad Il. 24. 6-9 ex.

“Those who marked these lines as spurious are not somehow crack-brained, since they take these lines as naughty and suspect verses like this—because he longs for a bed-mate, not in the style worthy of demigods nor even of half women? For if this is wholly suspect, then Patroklos would be his lover because he [Achilles] is younger and very beautiful.

The [verses are considered suspect] for these reasons. Manliness is the nature of the man. But he also says “noble menos” and the verb tolupeuse is not well put.”

οἱ δὲ ἀθετοῦντες τοὺς στίχους πῶς οὐκ ἐμβρόντητοι, ῥηματίων κακοσχόλως ἐχόμενοι καὶ τοιούτων ἐπῶν κατηγοροῦντες b(BE3E4)T ὅτι ὡς σύγκοιτον ποθεῖ, οὐχ οἷον ἡμιθέων, ἀλλ' οὐδὲ ἡμιγυναίκων ἄξιον <ὄν>; εἰ γὰρ ὅλως τοῦτο ὑπονοεῖν δεῖ, ἐραστὴς ἂν εἴη Πάτροκλος ὡς νεωτέρου καὶ περικαλλεστέρου. T ἀθετοῦνται δὲ διὰ ταῦτα· ἀνδροτὴς γάρ ἐστιν ἡ τοῦ ἀνδρὸς φύσις· εἶπε δὲ καὶ μένος ἠΰ (6). καὶ τολύπευσε (7) δ' οὐκ εὔκαιρον·

The second passage combines normative statements about poetics and ethics to explain why some ancient scholars athetized (literally “marked as out of place”) four of these lines. I have discussed elsewhere the relationship between Achilles and Patroklos and don’t need to belabor it further other than to say that the epic is at times unclear about their relationship, but this passage seems about as clear as it gets and resistance to its meaning is rooted in the normative values of audiences not epic itself.

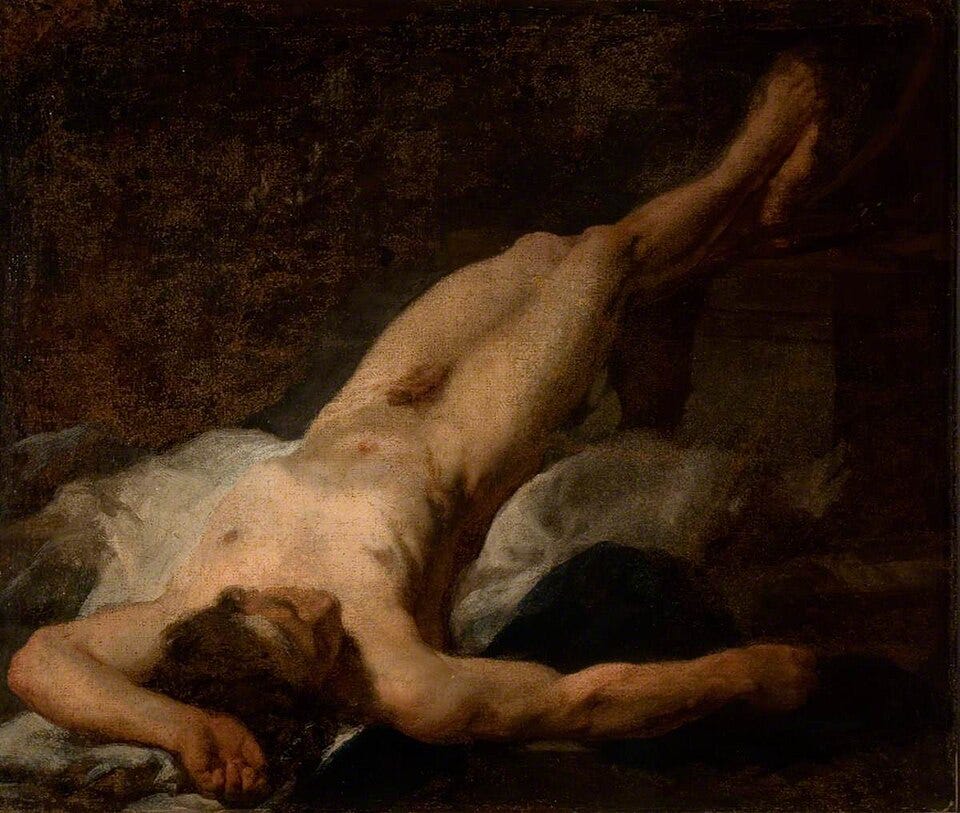

When it comes to the suggestion that these lines are “simplistic” in some way and therefore questionable, I am similarly skeptical of the scholia. I suspect in part that this claim is made as in indirect way of rejecting the depiction of Achilles longing for Patroklos in erotic or overly physical terms. Even if we take the criticism seriously, however, I think it falls apart. When I read this passage now, I find it to be a vivid depiction of a human being in grief, incapable of sleeping, turning over and over until they give up and go out and try to act in some way. Achilles is both unmoored by grief (he has no direction) but he is also stuck in sorrow’s time-loop: he keeps returning to the same actions (crying and then mistreating Hektor’s corpse) because he cannot move on.

There’s a psychological realism here rooted in human embodiment that reminds me of one of the fragments attributed to Sappho.

Sappho fr. 31

That man seems like the gods

To me—the one who sits facing

You and nearby listens as you

sweetly speak—and he hears your lovely laugh—this then

makes the heart in my breast stutter,

when I glance even briefly, it is no longer possible

for me to speak—but my tongue sticks in silence

and immediately a slender flame runs under my skin.

I cannot see with my eyes, I hear

A rush in my ears—A cold sweat breaks over me, a tremble

Takes hold of me. Then paler than grass,

I think that I have died

Just a little.”\φαίνεταί μοι κῆνος ἴσος θέοισιν

ἔμμεν’ ὤνηρ, ὄττις ἐνάντιός τοι

ἰσδάνει καὶ πλάσιον ἆδυ φωνεί-

σας ὐπακούεικαὶ γελαίσας ἰμέροεν, τό μ’ ἦ μὰν

καρδίαν ἐν στήθεσιν ἐπτόαισεν,

ὠς γὰρ ἔς σ’ ἴδω βρόχε’ ὤς με φώναι-

σ’ οὐδ’ ἒν ἔτ’ εἴκει,ἀλλ’ ἄκαν μὲν γλῶσσα †ἔαγε λέπτον

δ’ αὔτικα χρῶι πῦρ ὐπαδεδρόμηκεν,

ὀππάτεσσι δ’ οὐδ’ ἒν ὄρημμ’, ἐπιρρόμ-

βεισι δ’ ἄκουαι,†έκαδε μ’ ἴδρως ψῦχρος κακχέεται† τρόμος δὲ

παῖσαν ἄγρει, χλωροτέρα δὲ ποίας

ἔμμι, τεθνάκην δ’ ὀλίγω ‘πιδεύης

φαίνομ’ ἔμ’ αὔται·

Sappho’s language evokes the physical indica of desire and anxiety. It is vivid and serves to bridge a connection between the embodied experience of the audience and the poet’s song: The poem’s depiction of the body creates a common ground between the poet’s story and the audience’s experience. In the same way, I think that Achilles’ restless night attempts to bridge that gap between epic narrative and human life. The Homeric narrator’s language is less figurative and more direct than Sappho’s, but I think this is in part a function of the genre of lament, typically more staid and somber than lyric reflections on love imperiled. Life’s greatest losses leave us exhausted and empty, yet still rooted in that moment of separation. The bereft are locked between what was and the absence of what will be. The busy actions of rituals that are aimed at bringing initial closure to loss—funerals, funeral games, wakes, sitting shiva etc.—create a social framework for experiencing grief, but they don’t erase grief itself or fill the emptiness left behind.

This is a powerful moment because we see the epic hero undressed, in a way, bereft of the trappings of leadership, the actions of war, and the ritual frameworks that have kept him in motion right up until this moment. Achilles tossing and turning at night brings to bear on the audience the force of his loss in a way that anyone who has grieved can understand: no matter what happens during the day, night leaves us along with our grief, turning this way and that, trying to think of anything else and failing.

This in part explains Achilles’ return to Hektor’s corpse, a kind of regression to rage that is no longer there because rage filled him. When the scholion objects to the repetitions of words of remembering (μεμνημένος…τῶν μιμνησκόμενος), it is missing out on the structural framing that homes in on the act of memorialization, the work of narrative. Achilles’ grief issues from his memory’s interaction with his loss and the parenthetical structure echoes the inside/outside experience of narrative memory. Achilles is an audience to his own grief.

If this assertion seems tenuous, consider that this scene almost immediately reminds us that audiences are in fact observing Achilles’ lament. Apollo watches and pities Hektor (ἐλεαίρων). The gods act as indices for external audiences. Just as we are reminded of this as an audience, we are invited to consider the emotional experience, to weigh what it means to pity another, and to understand the impact that grief has on the human body.

Other posts Iliad 24

Disfiguring the Fallow Earth: Introducing Iliad 24: Divine Politics; the trial of Achilles; Apollo; Hesiod’s Theogony

"As If He Were Going to His Death": Priam and Katabasis in Iliad 24: Katabasis; Ransom; Structural echoes; Hermes and Orphism

"Blow Up Your TV": Thetis, Achilles, and Life and Death in Iliad 24: Thetis and grief; Gilgamesh; John Prine

Priam And Achilles, Pity and Fear: A 'tragic' end to Homer's Iliad: Cognitive approaches to Homer; Tragedy and Epic; Aristotle

Starving Then Stoned: Achilles’ Story of Niobe in Iliad 24: Paradeigmata, again; cognitive approaches to reading

"Better off Dead": Helen's Lament for Hektor in Iliad 24: Laments; Praise; Memory; Helen

The Burial of Horse-Taming Hektor: Ending the Iliad: Hektor; Aithiopis; Ending Epic; Ibycus; Pindar; Kleos