This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 24. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

In the last post on book 24, I wrote about how pity and wonder drive the actions of the epic’s close, furnishing both a resolution to many of the poem’s conflicts while also providing models for interpretation and ‘reading’, if not a foundation for ethical humanism. I focused in part on the mirroring and blending that happens in our relationship with narratives and proposed as well that the core function of pity in facilitating identification between Achilles and Priam through their recognition of each other’s suffering may also help to explain the ‘tragic’ core of the Iliad. By this I don’t mean simply that the Iliad follows a tragic arc, but that it also produces tragic effects in Aristotelian terms. Homeric epic, by modeling people seeing their own experiences and sufferings in other peoples’ lives and then articulating narratives with new understanding, clarifies the potential for narrative art to help us see more than ourselves in the world while also framing ourselves as part of a human and cosmic continuum.

This post follows on earlier posts positioning the meeting between Achilles and Priam as in a liminal space between life and death and on the importance of Thetis to the Iliad, especially when she gives advice to her son about taking the remaining time he has to enjoy what pleasure life has to offer. I bring these topics up because I think they are linked to the story Achilles tells Priam about Niobe and how we should interpret it.

Once Achilles and Priam have had their (temporary) fill of weeping, Achilles tries to encourage Priam to stay and share a meal with him. This meal-sharing is critical for Achilles on a symbolic level as a step in his return to acting like a human being instead of some kind of a wild animal or a god of war. Priam is reluctant because he wants to get Hektor’s body home for burial and he is rightly wary of being around Achilles too long. Achilles uses an interesting narrative of myth to ‘persuade’ Priam to join him.

Iliad 24.596-620

“And then shining Achilles went back into his dwelling

And sat on the finely decorated bench from where he had risen

near the facing wall. Then he began his speech [muthon] to Priam:‘Old man, your son has been ransomed as you were pleading—he

Lies now on the bedding. You will see him at dawn yourself

When you lead him away. But now, we should remember our meal.

For fair-tressed Niobê, too, remembered to eat,

Even though her twelve children perished at home.

Six daughters and six sons.

Apollo killed them with his silver bow

Because he was angry at Niobê, and Artemis helped too,

Because their mother had considered herself equal to fair-cheeked Leto.

She claimed that Leto birthed two children while she had many.

And so those mere two ended the lives of many.

They lingered in their gore for nine days and no one went

To bury them—Kronos’ son turned the people into stone.

On the tenth day, the Olympian gods buried them.

And she remembered to eat, after she wore herself out shedding tears.

And now somewhere in the isolated crags on the mountains

Of Sipylus where men say one finds the beds of goddesses,

Of the nymphs who wander along the Akhelôis,

She turns over the god-sent sufferings, even though she remains a stone.

So, come, now, shining old man, let’s the two of us remember

Our meal. You can mourn your dear son again

After you take him to Troy—he will certainly be much-wept.”῏Η ῥα, καὶ ἐς κλισίην πάλιν ἤϊε δῖος ᾿Αχιλλεύς,

ἕζετο δ’ ἐν κλισμῷ πολυδαιδάλῳ ἔνθεν ἀνέστη

τοίχου τοῦ ἑτέρου, ποτὶ δὲ Πρίαμον φάτο μῦθον·

υἱὸς μὲν δή τοι λέλυται γέρον ὡς ἐκέλευες,

κεῖται δ’ ἐν λεχέεσσ’· ἅμα δ’ ἠοῖ φαινομένηφιν

ὄψεαι αὐτὸς ἄγων· νῦν δὲ μνησώμεθα δόρπου.

καὶ γάρ τ’ ἠΰκομος Νιόβη ἐμνήσατο σίτου,

τῇ περ δώδεκα παῖδες ἐνὶ μεγάροισιν ὄλοντο

ἓξ μὲν θυγατέρες, ἓξ δ’ υἱέες ἡβώοντες.

τοὺς μὲν ᾿Απόλλων πέφνεν ἀπ’ ἀργυρέοιο βιοῖο

χωόμενος Νιόβῃ, τὰς δ’ ῎Αρτεμις ἰοχέαιρα,

οὕνεκ’ ἄρα Λητοῖ ἰσάσκετο καλλιπαρῄῳ·

φῆ δοιὼ τεκέειν, ἣ δ’ αὐτὴ γείνατο πολλούς·

τὼ δ’ ἄρα καὶ δοιώ περ ἐόντ’ ἀπὸ πάντας ὄλεσσαν.

οἳ μὲν ἄρ’ ἐννῆμαρ κέατ’ ἐν φόνῳ, οὐδέ τις ἦεν

κατθάψαι, λαοὺς δὲ λίθους ποίησε Κρονίων·

τοὺς δ’ ἄρα τῇ δεκάτῃ θάψαν θεοὶ Οὐρανίωνες.

ἣ δ’ ἄρα σίτου μνήσατ’, ἐπεὶ κάμε δάκρυ χέουσα.

νῦν δέ που ἐν πέτρῃσιν ἐν οὔρεσιν οἰοπόλοισιν

ἐν Σιπύλῳ, ὅθι φασὶ θεάων ἔμμεναι εὐνὰς

νυμφάων, αἵ τ’ ἀμφ’ ᾿Αχελώϊον ἐρρώσαντο,

ἔνθα λίθος περ ἐοῦσα θεῶν ἐκ κήδεα πέσσει.

ἀλλ’ ἄγε δὴ καὶ νῶϊ μεδώμεθα δῖε γεραιὲ

σίτου· ἔπειτά κεν αὖτε φίλον παῖδα κλαίοισθα

῎Ιλιον εἰσαγαγών· πολυδάκρυτος δέ τοι ἔσται.

One scholiast notes that the comparison is aimed at persuasion and that the adduction of similar suffering “lightens Priam’s” (ἐπικουφίζεται γὰρ τὰ πάθη, bT ad Il. 24.601 ex. 2) while another focuses on the logical way in which Achilles unfolds the tale. Yet the overwhelming ancient response is incredulity:

Schol. A ad. Il. 24.614-617a ex

“These four lines have been athetized [marked as spurious] because it does not make sense for her to “remember to eat” “after she wore herself out shedding tears.” For, if she had been turned into a stone, how could she take food?

Thus, the attempt at persuasion is absurd—“eat, since Niobê also ate and she was petrified, literally!” This is Hesiodic in character, moreover: “they wander about Akhelôion. And the word en occurs three times. How can Niobê continue pursuing her sorrow if she is made out of stone? Aristophanes also athetized these lines.”

Ariston. | Did. νῦν δέ που ἐν πέτρῃσιν<—πέσσει>: ἀθετοῦνται στίχοι τέσσαρες, ὅτι οὐκ ἀκόλουθοι τῷ „ἡ δ’ ἄρα σίτου μνήσατ’, <ἐπεὶ κάμε δάκρυ χέουσα>” (Ω 613)· εἰ γὰρ ἀπελιθώθη, πῶς σιτία προ<σ>ηνέγκατο; καὶ ἡ παραμυθία γελοία· φάγε, ἐπεὶ καὶ ἡ Νιόβη ἔφαγε καὶ ἀπελιθώθη. ἔστι δὲ καὶ ῾Ησιόδεια τῷ χαρακτῆρι, καὶ μᾶλλόν γε τὸ ἀμφ’ ᾿Αχελώϊον ἐρρώσαντο (616). καὶ τρὶς κατὰ τὸ συνεχὲς τὸ ἔν (614. 615). πῶς δὲ καὶ λίθος γενομένη θεῶν ἐκ κήδεα πέσσει (617); | προηθετοῦντο δὲ καὶ παρ’ ᾿Αριστοφάνει.

Schol. bT ad Il. 24. 614-617

“these four lines are athetized. For how could a stone taste food? Also, why does the poet place a river from Aetolia on Sipylos?”

ex. νῦν δέ που ἐν πέτρῃσιν<—πέσσει>: ἀθετοῦνται τέσσαρες· b(BCE3)T πῶς γὰρ ἡ λίθος τροφῆς ἐγεύσατο (cf. Ω 602. 613); b(BCE3E4)T τί δὲ ὁ Αἰτωλῶν ποταμὸς ἐνΣιπύλῳ ποιεῖ (cf. 616); T πῶς τε λίθος οὖσα κήδεα πέσσει (617)

The scholia note that the lines were athetized because it makes no sense for Niobê to stop eating during her destructive mourning; or, it is impossible to eat for one who has been turned to stone. And worse—one cannot mourn post petrifaction! In Achilles’ defense, he has selected an example from myth of a parent mourning the loss of a child; the loss has come at the hands of the gods who have sought to punish human transgression. In Achilles’ application of the tale, Niobê stops to eat—is this altogether absurd?

The effect of the scholiastic comments and the dissonance between what Achilles says here and what he has attributed to Niobê has led many scholars to argue that the lines about Niobê turning to stone are later “interpolations” by editors trying to explain the whole story. Authors like Johannes Kakridis (1930) and Thomas Pearce (2008) have made strong thematic arguments about why these lines shouldn’t be there. I think that some of what they say is reconcilable with multiform approaches to Homer like that explored by Casey Dué in Achilles Unbound, that these lines are legitimately part of telling the story of the Iliad, but perhaps were not present for all audiences. To my taste, these lines are necessary if people don’t know the story of Niobê because her turning into a stone is critical to the impact of the comparison. This is a very different perspective than others have offered, so I want to take a moment to explain.

Schol. bT ad. Hom. Il. 24.602a ex

“Some say that this Niobê is the daughter of Pelops; others say she is the daughter of Tantalos. Others claim that she is the wife of Amphion or of Zethus. Still more claim that she is the wife of Alalkomeneus. Among the Lydians she is called Elumê. And this event occurred, as some claimed, in Lydia; or, as some claim, in Thebes.

Sophokles writes that the children perished in Thebes and that she returned to Lydia afterwards. And she perished, as some claim, after she swore a false oath about the dog of Pandareus because [….] or later when she had been ambushed by the Spartoi in Kithaira. There were two Niobes, one of Pelops and one of Tantalus. He explains the whole tale because the story is Theban and unknown to Priam.”

ex. | ex. <καὶ γάρ τ’ ἠΰκομος Νιόβη:> τὴν Νιόβην οἱ μὲν Πέλοπος, οἱ δὲ Ταντάλου· γυναῖκα δὲ οἱ μὲν ᾿Αμφίονος, οἱ δὲ Ζήθου, [οἱ δὲ] ᾿Αλαλκομένεω. ἐκαλεῖτο δὲ παρὰ Λυδοῖς ᾿Ελύμην. ἡ δὲ συμφορὰ αὐτῆς, ὡς μέν τινες, ἐν Λυδίᾳ, ὡς δὲ ἔνιοι, ἐν Θήβαις. Σοφοκλῆς (cf. T.G.F. p. 228 N.2; II p. 95 P.) δὲ τοὺς μὲν παῖδας ἐν Θήβαις ἀπολέσθαι, νοστῆσαι <δὲ> αὐτὴν εἰς Λυδίαν. ἀπώλετο [δέ], ὥς τινες, συνεπιορκήσασα Πανδάρ[εῳ] περὶ τοῦ κυνός, ὡς δὲ [..], ἐνεδρευθεῖσα ὑπὸ τῶν Σπαρτῶν ἐν Κιθαιρῶ[νι]. οἱ δὲ δύο Νιόβας, Πέλοπος καὶ Ταντάλου. T | ὡς Θηβαῖον ὄντα τὸν μῦθον καὶ ἀγνοούμενον Πριάμῳ ἐπεξεργάζεται.

Yoshinori Sano (1993) has argued that the full account of Niobê helps to explore the isolation and loneliness of both Priam and Achilles. I think this is a really good argument and what I would like to add is that this isolation is in a crucial way synonymous with death. Homeric narrative provides multiple meanings—its polysemy is connected to a dynamic model of reading that I have tried to emphasize throughout the process of posting on the Iliad.

As I have discussed in earlier posts, paradeigmata like this—examples from myth offered to persuade an audience member—respond well to interpretations that use notions of cognitive blending like those presented by Mark Turner. Rather than assume a logical comparison between the worlds of the speaker, the audience, and the story, we have to see them as creative separate narrative blends

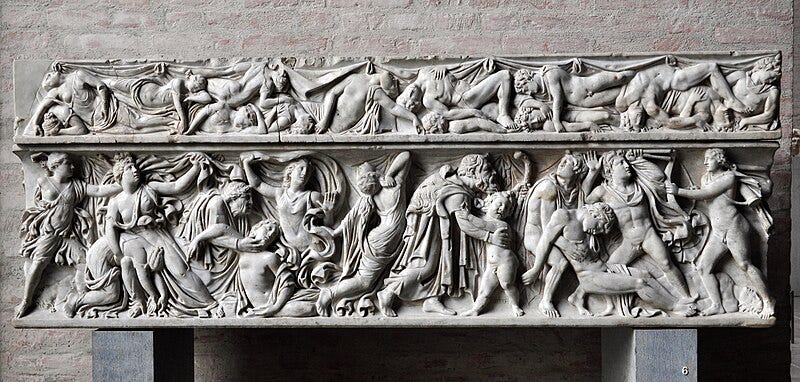

It certainly does not make logical sense for Niobê to eat—but there are other details in the narrative that can produce through projection from the target space a latticework within the creative blend. For instance, the pairing of a sequence of nine followed by resolution on the tenth recalls for the audience locally the recent delay of the gods in their argument over the burial of Hektor (24.108–109) and generally the nine and ten days of the plague at the epic’s inception (1.53–54) as well as the nine and ten years of the Trojan war itself. The looming finality of the tenth unit of time is emphasized through the petrifaction of the people in Achilles’ tale—an image that easily coalesces with Iliadic language about grave markers standing in place for a man after his death.

The clear input source from Achilles is that Niobê and Priam are similar—they have both lost children thanks to divine anger over human action. Achilles does not specify any wrongdoing on Priam’s fault (that occurs in Priam’s notional blend and in the audience’s imagination). In the repeated first-person plural injunction to eat (νῦν δὲ μνησώμεθα δόρπου… μεδώμεθα…/ σίτου, 601/618), moreover, there is an invitation to Priam (and to us) to allow Achilles himself into the creative blend—especially since he has so strongly refused to eat earlier in the poem (in book 19).

When we admit Achilles into the blend alongside Priam we as audience members may sense his (1) acknowledgment of impending death; (2) acceptance of some responsibility for his loss. If Niobê’s absurd break from mourning to eat creates an image-schematic clash, it may be an effective one: Priam lost more children over a longer period of time and will lose more still. Achilles is acknowledging the magnitude of their combined losses and that their story is not yet at its end. In now encouraging another to eat, Achilles offers another lesson about the necessity of living on despite the pain until life reaches its final closure.

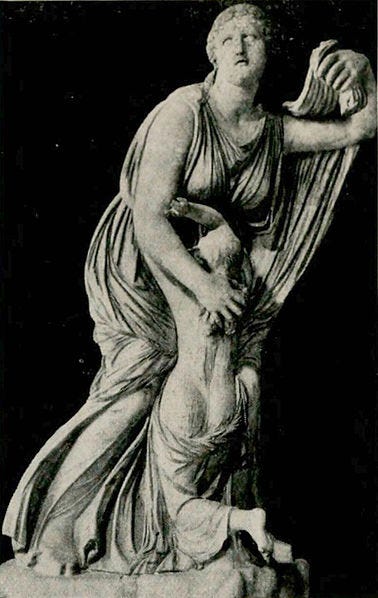

It is this last step where I think we can really understand how Achilles has learned, in this book alone. Recall the advice his mother gives him just 500 lines earlier: she tells him that it is good to take time to eat, to have sex, to enjoy life before its over. She offers this when everyone knows that Achilles’ life is foreshortened following the death of Hektor. But when Achilles applies similar wisdom to Priam through the story of Niobê, the jarring contrast is intentional: it uses a very extreme case to make a more general point.

Achilles has adapted his mother’s lesson to his understanding of an an earlier tale. Audiences knowing the story of Niobê turning to stone increases the force of the passage. Yes, she stopped mourning to eat. We all continue living amid scars, losses, and grief. Life goes on during war. Children are born during sieges and famines. People fall in love as their worlds fall apart. Life continues right up to the moment of death and whether the end is 5 minutes from now or five decades it is uncertain. We should take the time we can to eat and enjoy the pleasures life offers, where and when they appear.

Achilles forgot this after Patroklos died—in fact, we might even argue that he never learned this or else wouldn’t have lost his mind at a slight to his honor in book 1. To be fair, we all forget these truths in the repetitive busyness of life. Whether we have one day left or most of a lifetime, what matters is making it matter. But this doesn’t have to mean dying in glory for eternal renown. It can mean sharing a meal with another, stopping to feel the earth turn.

Achilles’ wisdom is hard won and brief and all the more precious for it. Book 24 shows him adapting a narrative to try to share a moment of life with his bitter enemy’s father despite every force trying to keep him from doing so. He can do this because he has learned to see himself in Priam’s world. And the lesson of the Iliad for us is twofold: we too should take what life gives us while we can—but we need to see ourselves in others to truly do so.

A short bibliography

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Ahern, Charles F.. “Two images of « womanly grief » in Homer.” Essays in honor of Gordon Williams: twenty-five years at Yale. Eds. Tylawsky, Elizabeth Ivory and Weiss, Charles Gray. New Haven (Conn.): Henry R. Schwab Publ., 2001. 11-24.

Andersen, Øivind. 1987. “Myth Paradigm and Spatial Form in the Iliad.” In Homer Beyond Oral Poetry: Recent Trends in Homeric Interpretation, edited by Jan Bremer and Irene J. F. De Jong. John Benjamins

Braswell, B. K. 1971. “Mythological Innovation in the Iliad.” CQ, 21: 16-26.

Combellack, F.M. 1976. “Homer the Innovator.” CP 71: 44-55.

Dué, Casey. 2018. Achilles Unbound: Multiformity and Tradition in the Homeric Epics. Hellenic Studies Series 81. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Edmunds, L. 1997. Myth in Homer, in A New Companion to Homer, edited by I. Morris and B. Powell, 415–441. Leiden.

Friedrich, Paul and Redfield, James. 1978. “Speech as a Personality Symbol: The Case of Achilles.” Language 54: 263–288.

Held, G. 1987. “Phoinix, Agamemnon and Achilles. Problems and Paradeigmata.” CQ 36: 141-54.

Johannes Theophanes Kakridis, ‘Die Niobesage bei Homer. Zur Geschichte des griechischen Παράδειγμα’, Rheinisches Museum für Philologie (1930) 113-122[JC1] .

Knudsen, Rachel Ahern. 2014. Homeric Speech and the Origins of Rhetoric. Baltimore.

Martin, Richard. 1989. The Language of Heroes: Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca.

Nagy, Gregory. 1996. Homeric Questions, Austin.

---,---. 2009. “Homer and Greek Myth.” Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology, 52–82.

Thomas E. V. Pearce, ‘Homer, Iliad 24,614-17’, Rheinisches Museum für Philologie, 151.1 (2008) 13-25[JC2] .

Pedrick, V. 1983. “The Paradigmatic Nature of Nestor’s Speech in Iliad 11.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Society, 113:55-68.

Walter Pötscher, ‘Homer, Ilias 24,601 ff. und die Niobe-Gestalt’, Grazer Beiträge , XII-XIII. (1985-1986) 21-35.

Turner, Mark. 1996. The Literary Mind: The Origins of Thought and Language. Oxford.

Willcock, M.M. 1967. “Mythological Paradeigmata in the Iliad.” Classical Quarterly, 14:141-151.

____,____. 1977, Ad hoc invention in the Iliad, HSCP 81:41–53.

Yoshinori Sano, ‘An interpretation of the Niobe-paradeigma: Iliad XXIV 602-620’, Journal of Classical Studies, 41. (1993) 14-23[JC3] .