This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 23. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

In the first post on Iliad 23, I provide a good deal of framing for understanding the funeral games from Patroklos from a thematic/political perspective. At some point, I think I planned to write a second post on that topic, detailing the exchanges during the chariot race as a recapitulation of the events in Iliad 1 and 2. I think that this work has largely been done and would refer to the bibliography there for further reading.

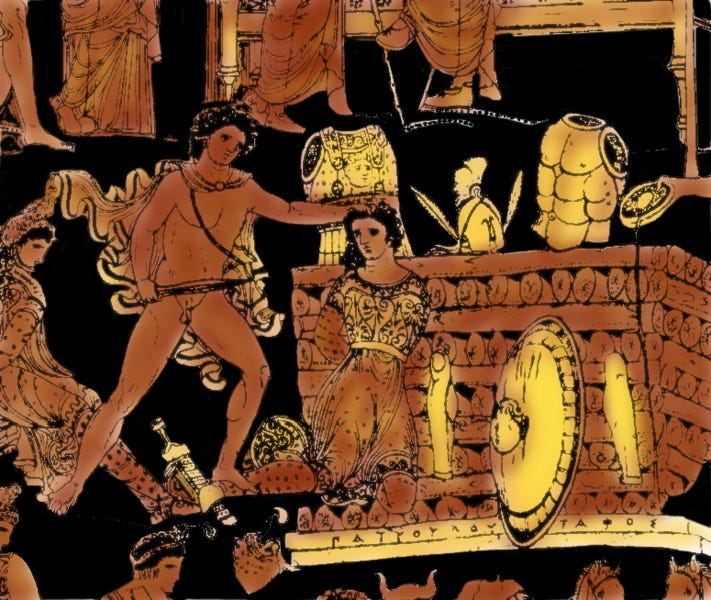

I remain interested—if not stuck—in how to understand the run-up to the games, which includes a lengthy burial ritual. This process is crucial for understanding Achilles’ character, but I think it can also help us think more about how epic poetry, about how much it tells and how much we assume it tells. The most prominent part of this, for me, is the human sacrifice that was promised in book 21. As I mention in that post, the seemingly casual presentation of the human sacrifice always reminds me of the murder of the suitors and the mutilation of the enslaved people in the Odyssey. Just as in that case, however, I think part of my/our sense that the acts are downplayed is connected to our cultural distance from ancient audiences.

As modern readers, we often find ourselves at a loss when it comes to evaluating epic actions without seeming terribly anachronistic or facing criticism for projecting our values on the past. The solution to this challenge is not maintaining neutrality, but allowing our responses to surface, interrogating them alongside the narrative, and using both ancient evidence and modern theoretical frameworks to ‘triangulate’ values. The point is not to cede evaluative ground, but to proceed with care, using transparency and owning our own perspectives to engage in a dialogue with the past rather than issuing a summary judgment.

My basic argument for both is that the non-combat murders that occur at the end of the Iliad and the Odyssey are certainly framed as excessive, if not transgressive, by each epic. These scenes contribute to an exploration of the dangers of the heroic figure who suffers and causes suffering. In the Odyssey, the slaughter functions, I think, to indicate the extremity of Odysseus’ vengeance and the stark violence endemic to autocracy. In the Iliad, we find the sacrifices as part of a narrative arc that takes Achilles far away from the realm of ‘civilized’ people and returns him again, if only briefly, to practices of reciprocity in book 24.

When I make arguments like this, I often encounter doubt, if not derision. This is why I think it is important to look at what the text does. In the case of the sacrifice of the twelve Trojan youths, the epic narrator marks it as “wicked” twice, once when the young men are captured in book 21 and again at the moment of their sacrifice in book 23. In between, Achilles calls them “glorious children of the Trojans, I am ready to sacrifice because I am angry over your death” (23.22-23). When we get to the act nearly two hundred lines later, the narrator is subtle, but to my mind clear.

Homer, Il. 23.161-191

Once Agamemnon, the lord of men, heard [Achilles]

He immediately dispersed the army to their fine ships,

While those who were close to Patroklos stayed by and piled the wood.

They made a pyre one-hundred strides wide to all sides,

And placed the body on the top of it, as they grieved in their hearts.

They flayed and butchered many sheep and in addition

Many ambling cattle in front of the pyre. Then great-hearted

Achilles took the fat from all of them and covered the corpse.

He heaped it over the body from head to toe.

Then he added to the rest large jars of honey and oil,

Leaving them next to the platform. He toppled four, high-necked horses

On the pyre quickly while he groaned outloud.

There were nine dogs who waited at the table for the lord,

And Achilles added two of them to the pyre, after cutting their throats.

He slaughtered the twelve sons of the great-hearted Trojans

With bronze. He was contriving wicked things in his thoughts.

And he kindled the iron-strong power of the fire, so he could spread it around.

Then, indeed, he mourned out loud and called his friend by name.

“Hello, my Patroklos, mine even in Hades’ home.

I am finishing everything that I promised to you before.

The fire is consuming all of these men for you—the twelve

Fine sons of the great-hearted Trojans. I will not give Hektor

Up to Priam to put in the fire. I’ll give him to the dogs.”So he threatened. But the dogs did not descend on Hektor.

No, Zeus’ daughter Aphrodite protected him from the dogs

All day and all night, keeping him anointed with rosy-olive oil,

Ambrosial stuff, so that he would not rip while being dragged.

And Phoebus Apollo cast over him a dark cloud

From the sky to the ground, and covered the whole land

Where the corpse stretched out, to stop the sun’s intensity

From drying out the skin still set on his muscles and limbs.Αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ τό γ’ ἄκουσεν ἄναξ ἀνδρῶν ᾿Αγαμέμνων,

αὐτίκα λαὸν μὲν σκέδασεν κατὰ νῆας ἐΐσας,

κηδεμόνες δὲ παρ’ αὖθι μένον καὶ νήεον ὕλην,

ποίησαν δὲ πυρὴν ἑκατόμπεδον ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα,

ἐν δὲ πυρῇ ὑπάτῃ νεκρὸν θέσαν ἀχνύμενοι κῆρ.

πολλὰ δὲ ἴφια μῆλα καὶ εἰλίποδας ἕλικας βοῦς

πρόσθε πυρῆς ἔδερόν τε καὶ ἄμφεπον· ἐκ δ’ ἄρα πάντων

δημὸν ἑλὼν ἐκάλυψε νέκυν μεγάθυμος ᾿Αχιλλεὺς

ἐς πόδας ἐκ κεφαλῆς, περὶ δὲ δρατὰ σώματα νήει.

ἐν δ’ ἐτίθει μέλιτος καὶ ἀλείφατος ἀμφιφορῆας

πρὸς λέχεα κλίνων· πίσυρας δ’ ἐριαύχενας ἵππους

ἐσσυμένως ἐνέβαλλε πυρῇ μεγάλα στεναχίζων.

ἐννέα τῷ γε ἄνακτι τραπεζῆες κύνες ἦσαν,

καὶ μὲν τῶν ἐνέβαλλε πυρῇ δύο δειροτομήσας,

δώδεκα δὲ Τρώων μεγαθύμων υἱέας ἐσθλοὺς

χαλκῷ δηϊόων· κακὰ δὲ φρεσὶ μήδετο ἔργα·

ἐν δὲ πυρὸς μένος ἧκε σιδήρεον ὄφρα νέμοιτο.

ᾤμωξέν τ’ ἄρ’ ἔπειτα, φίλον δ’ ὀνόμηνεν ἑταῖρον·

χαῖρέ μοι ὦ Πάτροκλε καὶ εἰν ᾿Αΐδαο δόμοισι·

πάντα γὰρ ἤδη τοι τελέω τὰ πάροιθεν ὑπέστην,

δώδεκα μὲν Τρώων μεγαθύμων υἱέας ἐσθλοὺς

τοὺς ἅμα σοὶ πάντας πῦρ ἐσθίει· ῞Εκτορα δ’ οὔ τι

δώσω Πριαμίδην πυρὶ δαπτέμεν, ἀλλὰ κύνεσσιν.

῝Ως φάτ’ ἀπειλήσας· τὸν δ’ οὐ κύνες ἀμφεπένοντο,

ἀλλὰ κύνας μὲν ἄλαλκε Διὸς θυγάτηρ ᾿Αφροδίτη

ἤματα καὶ νύκτας, ῥοδόεντι δὲ χρῖεν ἐλαίῳ

ἀμβροσίῳ, ἵνα μή μιν ἀποδρύφοι ἑλκυστάζων.

τῷ δ’ ἐπὶ κυάνεον νέφος ἤγαγε Φοῖβος ᾿Απόλλων

οὐρανόθεν πεδίον δέ, κάλυψε δὲ χῶρον ἅπαντα

ὅσσον ἐπεῖχε νέκυς, μὴ πρὶν μένος ἠελίοιο

σκήλει’ ἀμφὶ περὶ χρόα ἴνεσιν ἠδὲ μέλεσσιν.

We should start by noting how much this passage is doing. Consider the multiple mentions of grief and lamentation, making it clear that Achilles is in an extreme state of mind. The focus on the process of sacrifice may in part be a reflection on the importance of the ritual for processing grief. As anyone who has lost a loved one has learned, the concrete steps funerary rituals give us in the immediate days after our loss provides us with a feeling of control, of agency at a moment when we have been reminded that we ultimately have anything but that (over death). Rituals provide an outlet for grief, but they also importantly provide us with something to do. From a neurobiological perspective, sudden loss and extreme grief triggers a survival impulse: Achilles’ lashing out and slaughter is probably too ordered to simply be this, but his adaptation of ritual and his slowness to proceed may be a reflex of traumatic shock.

But to focus on the possibility of narrative judgment: the poem itself increases the importance of the human sacrifice by placing it in an ascending scale with the other victims. We start with the normal sheep and cattle, followed by the surprise dogs, ending with the twelve Trojan youths who are called “fine sons” of the great-hearted Trojans here, when they were referred as boys in book 21 and mere children before. The relevance of that choice increases for me: the label of sons enters them into families, into relationships that are torn by Achilles’ acts and the use of the adjective recalls the heroic language of nobility in the exchange with Lykaon in book 21 as well. Achilles repeats this line when he mourns later on, and a scholion reports that the adjective esthlous may have been replaced in some texts with a simple demonstrative toutous “these sons”).

Regardless of the repetition (or lack thereof), the narrative’s description is followed by the clearest line of judgment in the epic, the statement that Achilles is “devising wicked deeds” (κακὰ δὲ φρεσὶ μήδετο ἔργα·). If there is any doubt that there is something off about this sequence, following the speech, Achilles has trouble lighting the pyre and must appeal to the gods for help.

The cumulative effect of the rhetorical treatment (placing the slaughter at the end of a list, in the longest description), the familial and qualitative description of the youths, in contrast with earlier lines, the narrative judgment on the deeds, and the appearance of divine dissatisfaction, is to mark the sacrifice as extreme and as a feature of Achilles’ particular excess in his grief.

The view from outside

My reading of this scene requires a little more work to support. The cultural meaning of human sacrifice may be different for ancient audiences, and it is important to measure our response against what we can reconstruct from theirs. As Dennis Hughes writes in his introduction to Patroklos’ funeral (1991, 49), ancient authors were perplexed, if not horrified by this scene: “This incident so distressed Plato that he simply denied that Achilles had committed the deed, and the reactions of many modern Homeric scholars have been similar: shock and distaste (reactions sometimes projected back onto the psyche of Homer himself), a quick dismissal, or, more often than not, complete silence”.

The specter of human sacrifice overshadows the Iliad. The Trojan War narrative centers the sacrifice of Iphigenia to start the war, but other traditions also have the Trojan Polyxena sacrificed for/to Achilles as well. War itself demands a kind of sacrifice from soldiers, but the Iliad in particular sets up the Achaeans to be ‘sacrificial victims’ to Achilles’ honor while the surrogacy of Patroklos has something of a ritual substitution sacrifice to it. (Margo Kitts’ work is particular good at summarizing issues regarding sacrifice in the Iliad)

There have been questions for some time about to what extent Achilles’ sacrifice echoes historical practices. In addition to myths of human sacrifice in Athens, as well as in Sparta and Syracuse, and more broadly in myth among the family of Lykaon, or the self-sacrifice of the Lokrian Maidens, there is some archaeological evidence of human sacrifice in ancient Greece and theoretical speculation that ‘scapegoat’ narratives may have been related to ancient sacrificial practices. Herodotus mentions it too, but as an extreme. There is some caution here though: As Albert Henrichs suggests, the evidence for human sacrifice outside of Greece is far better than inside it, during the bronze age.

As Dennis Hughes argues, our interpretations have tended to imagine that this sacrifice was like other animal sacrifices or performed to provide Patroklos attendants in the Underworld and that the Iliad’s composers had lost knowledge about the practice. The other possibility—that Achilles’ act is meant as extreme, as an extension of his rage, is reconcilable with human sacrifice as an actual or forgotten practice. As Hughes notes, it seems difficult to argue that Homer is “downplaying” the incident when he mentions it three times, goes to great length to describe it, and then leaves the human portion of the sacrifice in the rhetorically marked, final position. It is perfectly possible that Achilles’ sacrifice is both an extreme outlet for his rage and a recognizable ‘ritual killing’ with real world antecedents.

This last point is important: As Henrichs argues, from the perspective of Greek myth and tradition, human sacrifice can happen but it is extreme and ritual killing “is something which uncivilized men inflict upon one another but which no Greek in his right mind with contemplate” (2019, 63). Achilles is steadily depicted throughout the Iliad as someone who has withdrawn from the communion of human beings, flirting with the excesses of the god of war when he is not descending to the animal realm. Tamara Neal demonstrates that Achilles has a particular blood-lust, marked even for the Iliad, shared with Ares and predatory animals in similes. His rage pushes him to animalistic and supernatural extreme, but at this moment in the epic, the sense seems more of irresolvable grief.

The excess of the sacrifice functions in part to characterize the agent of the act. As Sarah Hitch argues, sacrifices in the Iliad are subject to a system of reciprocity that emphasizes the status of the doer. The sacrifice in Iliad 23 is an evocation not just of the magnitude of Achilles’ grief, but the otherworldliness of his character. To my mind, it is part of a larger motif exploring the threat that figures like Achilles represent to their communities. Achilles’ life (and death) is one of cosmic proportion and significance. This sacrifice shows that his loss is too.

A short Bibliography on the sacrifice

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Emily P. Austin, Grief and the hero: the futility of longing in the Iliad. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021.

Bremmer, J. (1978) “Heroes, Rituals and the Trojan War,” Studi storico-religiosi 2, 5–38.

Burkert, W. (1966a) “Greek Tragedy and Sacrificial Ritual,” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies7, 87–121.

Clement, P. (1934) “New Evidence for the Origin of the Iphigeneia Legend,” L’Antiquité classique 3, 393–409.

Compton, Todd M. 2006. Victim of the Muses: Poet as Scapegoat, Warrior and Hero in Greco-Roman and Indo-European Myth and History. Hellenic Studies Series 11. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Graf, F. (1978) “Die lokrischen Mädchen,” Studi storico-religiosi 2, 61–79

Henrichs, Albert. "3. Human sacrifice in Greek religion: Three case studies". II Greek Myth and Religion, edited by Harvey Yunis, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2019, pp. 37-68. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110449242-003

Hitch, Sarah. 2009. King of Sacrifice: Ritual and Royal Authority in the Iliad. Hellenic Studies Series 25. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Hughes, Dennis. 1991. Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece. Routledge.

Kitts, Margo. “KILLING, HEALING, AND THE HIDDEN MOTIF OF OATH-SACRIFICE IN ILIAD 21.” Journal of Ritual Studies 13, no. 2 (1999): 42–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44368561.

Kitts, Margo. “SACRIFICIAL VIOLENCE IN THE ILIAD.” Journal of Ritual Studies 16, no. 1 (2002): 19–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44368624.

Lesser, Rachel. 2022. Desire in the Iliad: The Force That Moves the Epic and Its Audience. Oxford.

Mylonas, George E. “Homeric and Mycenaean Burial Customs.” American Journal of Archaeology 52, no. 1 (1948): 56–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/500553.

Neal, Tamara. “Blood and Hunger in the Iliad.” Classical Philology 101, no. 1 (2006): 15–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/505669.

Redfield, James R. The Locrian Maidens: Love and Death in Italy. Princeton, 2004.

Seaford, Richard. “Homeric and Tragic Sacrifice.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 119 (1989), 87-95

Hello Joel! Thank you for writing a great insight in this article! I have one question though, may I know whose translation you used for the Book 23 there? Was it self translation? I really love the choices of words and wishes to read more! Thank you.