This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations. Don’t forget about Storylife: On Epic, Narrative, and Living Things. Here is its amazon page. here is the link to the company doing the audiobook and here is the press page. I am happy to talk about this book in person or over zoom.

Patroklos leaves Achilles in book 11 to go investigate the wounded Achaeans and does not return until book 16. When he appears, he is described as weeping. And we hear two similes to describe how he weeps, one from the narrative and another from Achilles himself.

Homer, Iliad 16.1-11

“That’s how they were fighting around the well-benched ship.

Then Patroklos stood right next to Achilles, shepherd of the host,

Letting warm tears fall down his face as a dark-watered spring would,

One that pours murky water down a steep rock face.

When Achilles saw him, he pitied him

And spoke to him, addressing him with winged words.

“Patroklos, why are you crying just like a girl,

A young one, who rushes after her mother asking to be picked him,

Always grabbed her clothes and holding her back as she rushes—

She looks at her mother while crying so she will pick her up.

Patroklos, you’re shedding a tender tear like her.”῝Ως οἳ μὲν περὶ νηὸς ἐϋσσέλμοιο μάχοντο·

Πάτροκλος δ’ ᾿Αχιλῆϊ παρίστατο ποιμένι λαῶν

δάκρυα θερμὰ χέων ὥς τε κρήνη μελάνυδρος,

ἥ τε κατ’ αἰγίλιπος πέτρης δνοφερὸν χέει ὕδωρ.

τὸν δὲ ἰδὼν ᾤκτιρε ποδάρκης δῖος ᾿Αχιλλεύς,

καί μιν φωνήσας ἔπεα πτερόεντα προσηύδα·

τίπτε δεδάκρυσαι Πατρόκλεες, ἠΰτε κούρη

νηπίη, ἥ θ’ ἅμα μητρὶ θέουσ’ ἀνελέσθαι ἀνώγει

εἱανοῦ ἁπτομένη, καί τ’ ἐσσυμένην κατερύκει,

δακρυόεσσα δέ μιν ποτιδέρκεται, ὄφρ’ ἀνέληται·

τῇ ἴκελος Πάτροκλε τέρεν κατὰ δάκρυον εἴβεις.

The first simile is a repetition of sorts (and may be formulaic): Agamemnon is said to be crying like a stream before he speaks at the beginning of book 9 (14-15). The second part is somewhat more remarkable: from my experience, readers often infer the kinds of misogynistic statements that are typical in Homer (e.g. “Achaean women, not Achaean men, since you are cowards!...”) and in our own time (“fight like a girl”). One could be forgiven for assuming a kind of emasculation intended here on Achilles’ part.

The language outside the simile, however, may countermand such a reading. The narrator tells us that Achilles is pitying Patroklos (ᾤκτιρε) and the ‘winged words’ speech introduction often includes speech-acts that try to do things (although the fill intention of this speech is unclear). The content of the speech may have surprised ancient audiences as well: a scholion reports that Aristarchus preferred θάμβησεν (“felt wonder at”) instead of pitied. The scholia also question whether or not it is strange for Achilles to mock Patroklos for crying when Achilles himself was lamenting over losing a concubine (ἄτοπός ἐστιν αὐτὸς μὲν ἕνεκα παλλακίδος κλάων (cf. Α 348—57), τὸν δὲ Πάτροκλον κόρην καλῶν ἐπὶ τοιούτοις δεινοῖς δακρύοντα, Schol. bT ad Hom. Il. 16.7 ex).

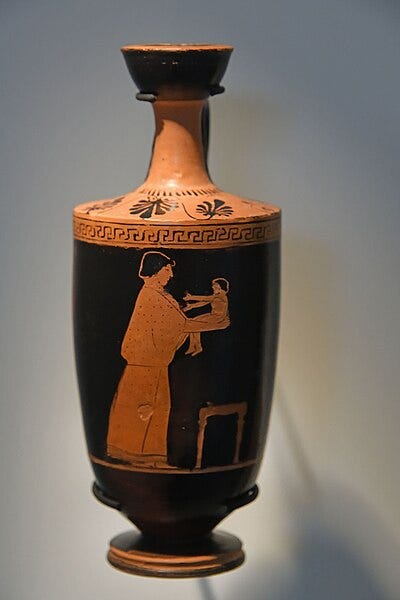

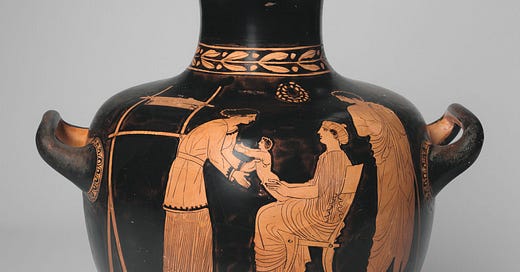

But how does our reception of this scene change if we don’t focus on the routine misogyny? One crucial thing the structure of the speech does for us–in addition to providing us a framework that shows this is not straight invective–is provide the contrast between how the narrator asks us to view Patroklos and how Achilles does. The narrator provides a repeated somewhat bland comparison to a fountain. But Achilles enlivens and personalizes the comparison. We cannot forget that in this simile, Achilles makes himself the mother.

One of my favorite takes on this comes from Celsiana Warwick’s great article “The Material Warrior: Gender and “Kleos” in the Iliad”. Warwick combines this with Achilles’ description of himself in book 9 as a mother bird trying to bring food to her chicks. In that simile, Achilles compares the whole army to the chicks looking to him for food. Warwick writes:

The image of the mother ignoring the needs of her child represents the way in which Achilles at this point in the poem is ignoring the needs of the Achaeans, whom he described as his children at 9.323–7. Achilles’ use of this simile here should thus not be regarded as incidental, but rather as part of his larger pattern of maternal identification. In Book 9 the mother bird is self-sacrificing, directing all of her attention towards her chicks. In the second simile, a change has taken place in Achilles’ conception of himself as a mother; now he has turned his back on the child and moves away from her. The scene, although domestic and familiar rather than destructive or threatening, highlights Achilles’ refusal in Book 16 to take up his protective role. It foreshadows the destructive consequences of this refusal, especially when juxtaposed with the simile of the mother of the chicks. The gender dynamics of this image are also intriguing; although the comparison of Patroclus to a foolish girl appears to be negative, Achilles does not seem to impugn his own masculinity by associating himself with the mother.

By situating this image along with other comparisons to women in Homer–e.g. Heroic pain compared to women in childbirth, or heroes compared to animal mothers and offspring–Warwick argues that maternity is associated with protection in Homer, implying, perhaps, an obligation to shelter others that yields a greater level of pain and suffering when warriors fail to do so. Consider the existential pain felt by Thetis in response to her inability to save her son or the emphasis Andromache puts on imagining her son’s (impossible) futures. The language of each simile, moreover, strengthens these connections: As Casey Dué demonstrates, Achilles’ similes resonate with women’s laments in the epic tradition. In a way, they are proleptic, priming an audience that already knows the events of the story to see Achilles’ actions in a certain way. The associations may be broader than this too–Cathy Gaca has suggested that the simile recalls the image of a mother and child fleeing a warrior during the sack of a city.

This associative framework is especially effective for exploring Achilles’ actions because he fails in his role as a protector. Warwick adds, “It is particularly appropriate for Achilles to compare himself to a mother because maternity, unlike paternity or non-parental divine protection, is closely linked in Homeric poetry with the mortal vulnerability of human offspring.” Achilles becomes a “murderous mother” who is a direct cause of Patroklos’ death.

This simile and Achilles’ own self-characterization increases the pathos of his story. This is echoed and reinforced–as Emily Austin argues well in her article (Grief as ποθή )--when Achilles’ grief over Patroklos’ death is compared to a mother lion’s sorrow over the loss of her cubs. In addition to these powerful connections between women and the life cycle, these images also underscore the impact that heroic violence has on familial relationships. The Achaeans at Troy do not have their families with them (with some exceptions): the consequences of war fall most heavily on women and children. This simile can both humanize Achilles and vilify him. The greater we understand his feelings of love and responsibility for Patroklos, the more horrifying it is when we understand that Achilles himself ultimately prayed for his own people to die.

We also have to attend to the impact on Patroklos: if Achilles is trying to do something with this speech, what is it? Jonathan Ready suggests that Achilles is letting Patroklos know that he is there and, like a mother, will eventually take care of her child. I like this reading, but I wonder if there isn’t a clash between Achilles’ belief that he can comfort Patroklos and the image itself which remains unresolved. The child in the simile goes on, tugging, wanting to be picked up, but never fully heard. We must imagine, I think, that Achilles sees these actions as being completed outside the simile when he listens to Patroklos and responds. As Rachel Lesser suggests, Patroklos is not fully heard. Patroklos’ “appeal represents a challenge to [Achilles’] will” (175). Achilles is troubled and upset by his friend being upset; but he is also conflicted by what he asks. Like a frustrated, harried mother who finally picks up the persistent child, Achilles concedes to Patroklos, but with demands and limits that will make neither of them happy.

I think this passage provides a great sample of how hard it can be to interpret Homer and how many different ideas need to be balanced at once. The scholars I have mentioned weigh cultural ideas about gender and relationships against what actually happens in the Homeric poems and generate a series of responses that point to the sensitivity and open-endedness of the simile. Achilles frames himself and Patroklos as a matter of expressing their relationship to one another, his view of the situation, and, perhaps more deeply, a troubled sense of responsibility. The lack of resolution in the simile and the striking image itself draws the audience’s attention to the moment, encouraging us to think through the image and make sense of it on our own.

Other Posts on Iliad 16

Iliad 16

There's Plenty of Crying in Epic: Introducing Book 16: Achilles and Patroklos (Patrochilles); surrogacy

Even Zeus Suffers: The Death of Sarpedon and the Beginning of Universal Human Rights: Death and Funeral rites; Mortals and gods

Merely the Third To Kill Me: Hektor, Patroklos, and the End of Iliad 16: Apostrophe; prophecy; narrative traditions

A short bibliography on this simile

Austin, Emily. “Grief as ποθή : understanding the anger of Achilles.” New England Classical Journal, vol. 42, no. 3, 2015, pp. 147-163.

Dué, Casey. “Achilles, mother bird: similes and traditionality in Homeric poetry.” The Classical Bulletin, vol. 81, no. 1, 2005, pp. 3-18.

Gaca, Kathy. 2008. “Reinterpreting the Homeric Simile of Iliad 16.7–11: The Girl and Her Mother in Ancient Greek Warfare.” AJP 129: 145–71.

Ledbetter, Grace. 1993. “Achilles’ Self-Address: Iliad 16.7–19.” AJP 114: 481–91.

Lesser, Rachel. 2022. Desire in the Iliad. Oxford.

Mills, Sophie. 2000. “Achilles, Patroclus and Parental Care in Some Homeric Similes.” G&R 47: 3–18.

Pratt, Louise. 2007. “The Parental Ethos of the Iliad.” Hesperia Supplements 41: 25–40.

Ransom, Christopher. 2011. “Aspects of Effeminacy and Masculinity in the Iliad.” Antichthon 45: 35–57.

Ready, Jonathan. 2011. Character, Narrator, and Simile in the Iliad. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Warwick, Celsiana. “The maternal warrior: gender and « kleos » in the « Iliad ».” American Journal of Philology, vol. 140, no. 1, 2019, pp. 1-28. Doi: 10.1353/ajp.2019.0001

I was noticing that the word νήπιος was applied twice to Patroclus in this early part of 16: first, according to Achilles, Patroclus is the silly (adjective, feminine) young girl weeping to be picked up [16.8]; second, according to the narrator, he’s a fool (noun, masculine) pleading with Achilles to grant what would result in his own destruction [16.46].

To Achilles, Patroclus is begging for safety and salvation; to the narrator, he’s begging for destruction.