This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. Following the completion of book-by-book posts entries will fall into three basic categories: (1) new scholarship about the Iliad; (2) themes: (expressions/reflections/implications of trauma; agency and determinism; performance and reception; diverse audiences); and (3) other issues of texts/transmission/and commentary that occur to me. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

When I was in graduate school, the late Seth Benardete used to tell students that you had never really read the Iliad unless you read it in a week (in Greek). For the longest time, I took this as a general baseline goal. I have accomplished it a few times, at first having to put in 8-10 hour days to finish in a week, but later being able of covering the daily portion in 4-5 hours of reading.

Being able to read Homer at that pace indicates a fluency that is about as close to my native reading pace as possible. Such fluency and the greater speed helps you see connections across books and sections that you might miss at a more leisurely pace. Moving through 4-6 books a day in Greek requires a mastery of both morphology and vocabulary. Yet, speed doesn’t always mean reading well. Indeed, there’s a bit of tension between Friedrich Nietzsche’s assertion that philology is the “the art of reading well” (die Kunst gut zu lesen) and Roman Jakobson’s later suggestion that “philology is the art of reading slowly.”

My current response to Benardete’s injunction is somewhat more complicated. I think he’s probably right that the mastery of language needed to really understand the Homeric epics and the capacious understanding of the whole poem are demonstrated through such a marathon-reading. (Indeed, while I do think for most topics in the ancient world, advanced language training is no longer required, I am on the record insisting that for literary study it is. One can talk about Homer without reading the epics in Greek, but any sustained engagement with the epics as narrative literature requires a study of the language as well.)

But I also think that there is something important in changing paces. One sees differently based on speed: I often try to impart this to students by getting them to think through what they notice and experience differently if they walk, run, or drive along the same route. Cognitively, we see different shapes and notice different patterns–and there’s an embodied effect to this too. We feel the world (and texts) through our own cadences. Checking in on both when our speed changes is like looking at a piece of visual art from different angles, in different light.

I have come to be more convinced that the most important way to engage with the Homeric epics is duratively, changing paces, changing focus from time to time. In part, this comes from an awareness that the “read it in seven days” goal is as much about developing and demonstrating linguistic mastery as it is about treating Homeric epic like a modern novel. Once the former is achieved, the appropriateness of the latter should be questioned.

I am more and more convinced that ancient readers rarely ever read the whole epic and that when they did ‘read’ the way we do, they read episodes and pre-selected passages. Similarly, when the Homeric epics were primarily part of performance culture, I think most audiences heard only bits and pieces over their lives with rare opportunities to think about the whole. So, to my mind, one should always be reading Homer, finding space for the bits and pieces where we can, and carving out time for the longer engagement too.

My practice has long been to think through problems in either epic, to sample episodes and passages trying to understand my intuitive response to certain issues, and then, once I think I have an idea, to test it by reading the epic from beginning to end (again). When I re-read in this way, I tend to read more slowly, because I am looking for different things, as if tracking an animal in the wild or re-tracing steps for something I have lost.

When I set up now, I use three screens like this.

I have an older application running the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, providing the Greek text, the Erbse edition of most of the scholia, the Van Thiel pdf of the D scholia, and then, just in case, the new version of Logeion (which is stupendous). For the most part, I can read without too much trouble, relying on glosses in the D scholia. What I have lost in vocabulary retention (all those hapax legomena!), I have gained in my greater knowledge of Greek outside Homer. So, like some monk in the Byzantine Renaissance, I can mostly make my way through things using the D Scholia. But Logeion is great for non-Homeric words and the odd form that has slipped this middle-aged mind.

But, wait, there’s more! As I discuss in the early post “Free Tools for Reading Homer’s Iliad,” the next generation of Perseus SCAIFE Viewer is really useful. In fact, it has the promise of one ay replacing most of what I have in my three screens above, although it still remains a bit clunky. The advantage over time will be the building of customizable widgets in the right-hand colum.

Much of what I can do using the TLG and the scholia is also possible combining the Scaife viewer with the Homer Multitext Project (HMT), which provides manuscript variants, different scholia, and the ability to choose different views.

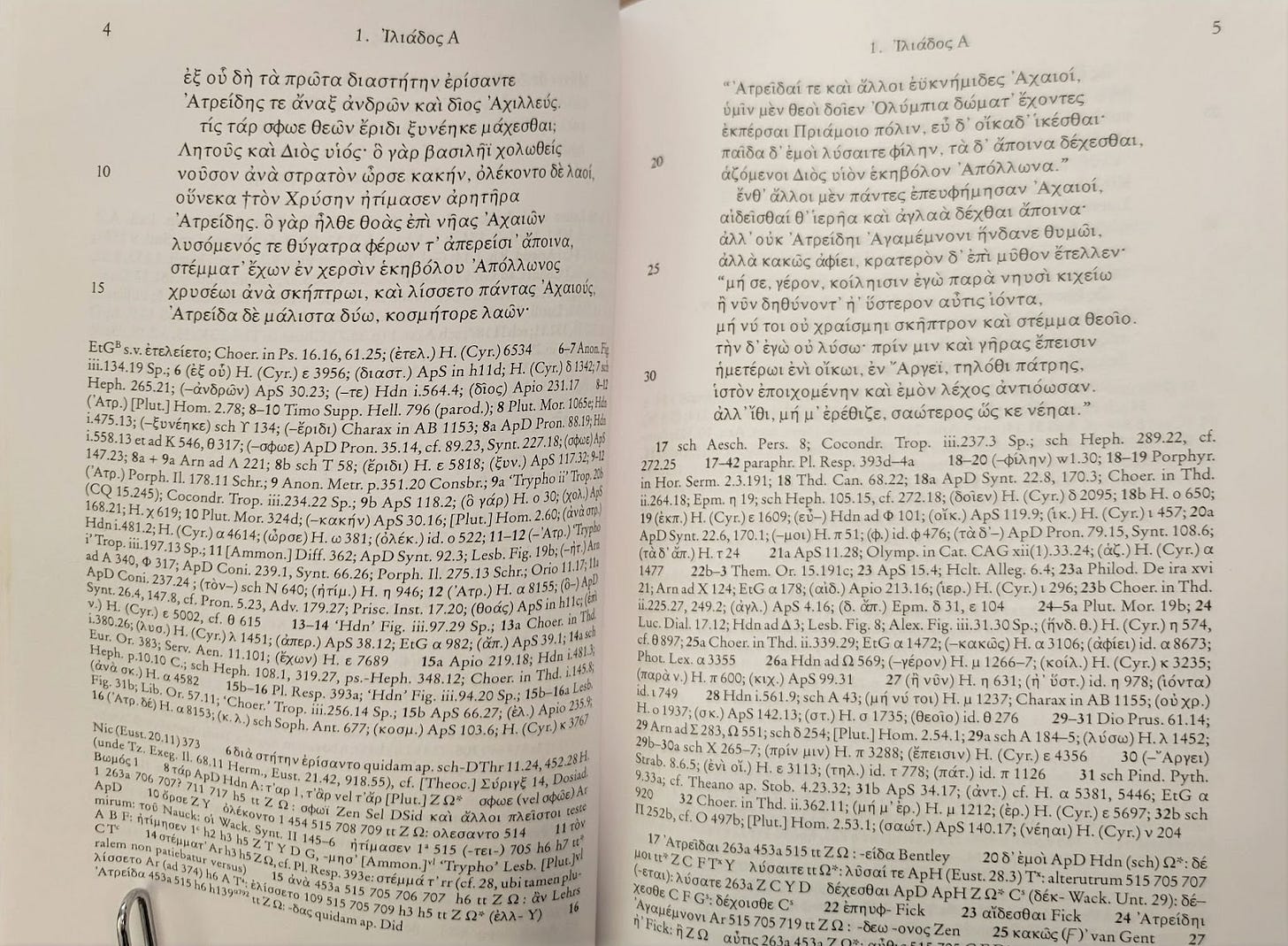

Together with the SCAIFE viewer, the HMT can help address the most glaring problem of digital texts of Homer in the TLG and Perseus, and that is the singular nature of the text. Both formats present the epics as if the texts are standardized and simple. Here’s a picture of M. L. West’s Teubner.

The two sets of notes below the text themselves are testimonia (references to places where these lines are mentioned) and a more traditional textual apparatus that lists manuscript variants. None of this material is available from digital texts like the Loeb or TLG. Even this material is complicated, though: as anyone who does a deep study of the texts will learn, editors can ignore readings in some manuscripts, report a multiplicity of attestations for one reading in a misleading way, or ‘downgrade’ a reading by not representing how common it is. The apparatus gives the appearance of authority and inclusion, without actually having to be so.

So, when I sit down and start working through the Iliad to explore/test an idea, I create something like a hybrid-virtual medieval book wheel. I don’t always check all the sources, but I like to have the option to do so. And, to be honest, it is also a pleasure to work like this. Too often in modern discussions of reading and scholarly practices, we focus on the mission and the outcome, losing sight of the fact that many of us were drawn to this work because there is also a kind of pleasure in the process. For me, reading Homer becomes a bit of an unexpected journey on its own. When I am not applying the forced march method, I like to wander and meander, following up the paths and clues that speed forbids.

For those who want to download tools to a computer or tablet, here are some of my favorites:

On the TLG site you can access Cunliffe’s Lexicon of the Homeric Dialect.

Walter Leaf’s Commentary on the Iliad is available through Perseus. Three are downloadable versions through the HathiTrust.

Homer’s Iliad edited by Monro and Allen (the OCT Text)

Helmut van Thiel’s edition of the D. Scholia: a clean and easy to read FREE pdf with far more of the D Scholia than are included in the TLG. Dindorff’s Scholia to the Iliad can also be downloaded

Benner’s Selections from Homer’s Iliad” a great introductory text with grammar and vocabulary

Cunliffe’s Lexicon of the Homeric Dialect

What do you make of the idea of Pharr that one could learn Ancient Greek via starting with the Homeric poems as opposed to just starting with Attic Greek as a foundation and then progressing on to it?