This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

A year ago I started Painful Signs and then proceeded to write a series of posts about each book of the Iliad and then I turned to additional posts about Homeric scholarship. There’s plenty to do with the latter category still, but I also wanted to turn back to the books of the Iliad this year with a new post about each one, filling in some of the subjects I didn’t talk about.

Whether I like it or not, my relationship with the Iliad has been something like a Socratic dialogue: I keep getting to the end and realizing that I haven’t answered my questions, so there’s no recourse but to go back to the beginning again. (A process that has now occupied 25 years.) These posts will be weekly (I hope) and random, except that I am starting again with book 1 and moving through the next 24 weeks, saying something about each book.

In my earlier posts, I really don’t talk about much past Nestor’s intervention, which means I haven’t written about 60% of Iliad 1. One of the things I have been rethinking in my passes through the epic is about how Achilles sees the world around him, about the limits on his own understanding of the essential realness of others, how he conceives of them primarily as objects and not agents (in grammatical and philosophical senses. This concern dovetails with the epic’s consciousness of the power of narrative and its interest in treating the viewing of internal audiences.

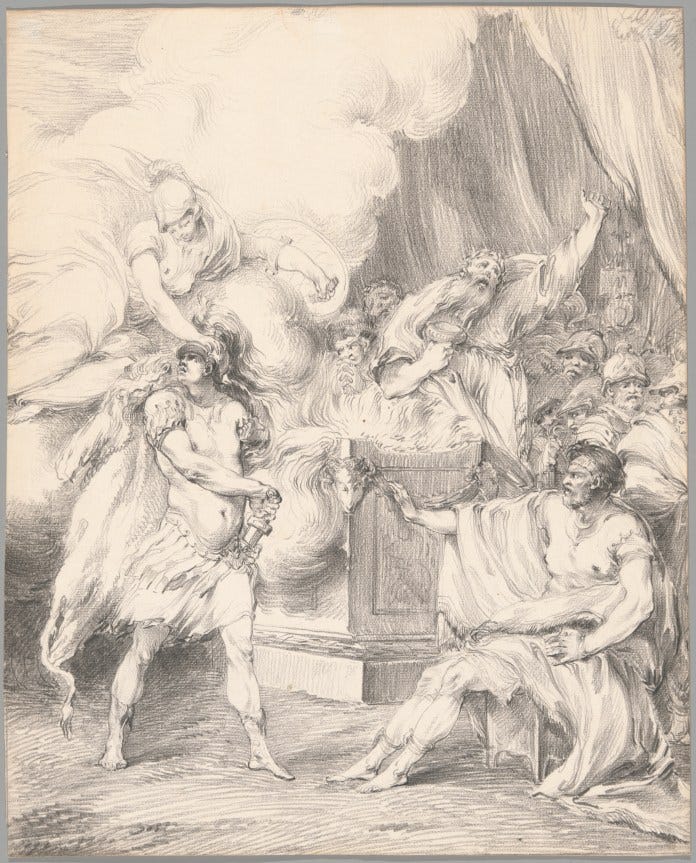

Achilles—like most of us—attributes motivations to others. He interprets the world and his misinterpretations often have disastrous effects. During a famous scene in book 1, I think we can see a strategy for managing and redirecting this tendency.

Iliad 1.202-204

“Why have you come here, child of aegis-bearing Zeus?

Is it so that you may see the hubris of Agamemnon, Atreus’ son?

But I declare this and I think it will happen this away:

He is going to destroy his own life soon because of his arrogance.”τίπτ’ αὖτ’ αἰγιόχοιο Διὸς τέκος εἰλήλουθας;

ἦ ἵνα ὕβριν ἴδῃ ᾿Αγαμέμνονος ᾿Ατρεΐδαο;

ἀλλ’ ἔκ τοι ἐρέω, τὸ δὲ καὶ τελέεσθαι ὀΐω·

ᾗς ὑπεροπλίῃσι τάχ’ ἄν ποτε θυμὸν ὀλέσσῃ.

When people think about Greek myth—and heroes in particular—they often bring up the concept of hubris, that excess of behavior, be it a specific act of outrage or a general demeanor, that is often mischaracterized as a kind of character ‘flaw’. (See this brief post about why the tragic flaw is a misunderstanding.) And while any reasonable reader can certainly see the thematic patterns of excess and arrogance as significant to the Iliad, the word itself appears sparingly in the epic. Of its four occurrences, two appear in Achilles’ exchange with Athena as he briefly considers just killing Agamemnon during the conflict in book 1.

One of the topics I am probably too obsessed with in my re-reading(s) of the Iliad is the extent to which characters are narrativizing their lives. What I mean by this are those scenes where it is either clear or arguable that we as audience members might imagine Homeric characters as acting under the influence of stories. This is what I think happens in book 9 when Achilles is seen singing the stories of famous heroes and then reinterprets Phoinix’s story of Meleager.

In addition to clear moments where external stories are implicated in the shaping (or misshaping) of the Iliad’s tale, I think we can also take some cues from moments of clear theatricality. Here, I don’t mean excessive behavior or histrionics, but those moments where the observation of a character’s action is shown to be determinative in the viewer’s subsequent behavior. This is ‘dramatic’ in the sense that it provides a show to be watched and interpreted by others; but it is also meta-mimetic, in that it inspires a change of action in the viewer, either in mirroring or reflecting on the action being seen.

In this later category, I have in mind Achilles’ lamentation for Patroklos that inspires similar emotions and actions from the epic’s internal audiences (both other Achaeans and the gods) or the final scene between Priam and Achilles that builds on those earlier exchanges, where Achilles and Priam feel pity and through sympathy identify with each other’s essential humanity, even if only briefly. In my current reading of this movement, Achilles’ extreme position as an elevated hero renders all of his actions larger-than-life with corresponding consequences. The epic strains to show the damage of Achilles self-absorption and how hard it is for him to see in others the suffering he recognizes in himself. While he weeps for Patroklos in book 19, he still primarily laments his own loss; when he identifies with Priam in book 24, he has a fleeting moment of self-transcendence, a humanizing instant. The epic’s point—I think—is both that such moments are possible and necessary to transcend our selfish violence but also that they are very hard to achieve, and nearly impossible to do so if everything about your own identity leads you to center yourself and your experiences to the detriment of all else in the world.

In re-reading the Iliad again, one of the things I am contemplating is the extent to which everyone ‘manages’ Achilles’ feelings and expectations. When Athena arrives, he asks her a direct question and makes it very clear what he thinks is going on. Athena’s response is a careful study in effective ‘de-escalation; another way to put it, is that she ‘manages’ Achilles by using his concepts and words and then forestalls the satisfaction of his rage by redirecting him.

“I have come for the purpose of slowing your anger, if you’ll consent,

From the sky. Hera, that white-armed goddess sent me,

Since we both love you and care about you in our hearts.

But, come, lay off the conflict, don’t draw your sword to hand.

But rebuke him with words about how it will turn out.

For I am declaring this and this is what will happen:

At some point you’ll get three times as many glorious gifts

In exchange for this outrage. But you, hold back. Listen to me.ἦλθον ἐγὼ παύσουσα τὸ σὸν μένος, αἴ κε πίθηαι,

οὐρανόθεν· πρὸ δέ μ’ ἧκε θεὰ λευκώλενος ῞Ηρη

ἄμφω ὁμῶς θυμῷ φιλέουσά τε κηδομένη τε·

ἀλλ’ ἄγε λῆγ’ ἔριδος, μηδὲ ξίφος ἕλκεο χειρί·

ἀλλ’ ἤτοι ἔπεσιν μὲν ὀνείδισον ὡς ἔσεταί περ·

ὧδε γὰρ ἐξερέω, τὸ δὲ καὶ τετελεσμένον ἔσται·

καί ποτέ τοι τρὶς τόσσα παρέσσεται ἀγλαὰ δῶρα

ὕβριος εἵνεκα τῆσδε· σὺ δ’ ἴσχεο, πείθεο δ’ ἡμῖν.

Athena doesn’t mince words to start: she tells Achilles’ what she is there to do (stop his wild behavior) and explains the authority behind her actions (Hera and herself). She uses direct imperatives to avoid any confusion and mirrors the structure of his speech: he makes a prediction (or a threat) and she makes a promise that he will receive more later. Only after using these strategies does she return to Achilles’ own language (hubris), using a demonstrative to acknowledge his views, without specifying the behavior that qualifies as such.

The reason I think this is a moment of narrativization is that Achilles expects a reaction from the gods for a certain kind of behavior: cosmic offense against the gods (i.e., hubris) is punished by divine will. To my reading, Achilles complains of a cosmic wrong to his being that is analogous to stories of myth. He sees Agamemnon as an arrogant mortal striving against a heroic demigod and articulates his expectation of divine recompense at Athena’s arrival. (We may even imagine him as anticipating the comeuppance himself and then reassigning the role to Athena when she appears).

We should not underestimate the importance, then, when Athena characterizes the issue as one of strife (eris). Achilles presents the situation using one kind of a mythical script: mortal commits hubris receives divine punishment. But Athena restates the experience using a different script: mortals involved in eris over a distribution of goods. Her promise that Achilles will receive three times more his lost compensation assures Achilles that Agamemnon has done wrong, but her framing of the situation shifts it from one story pattern to another.

Here are earlier posts on book 1:

Iliad 1

1. The Politics of Rage: Some Reading Guidelines for Iliad 1: Politics

2. Speaking of Centaurs: Paradeigmatic Problems in Iliad 1: On paradeigmata in book 1 and the Iliad

3. Prophet of Evils: Reading Iphigenia Into and Out of the Iliad: A first post on the Iliad’s relationship with other myths