This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 5. Here is a link to the overview of book 4 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

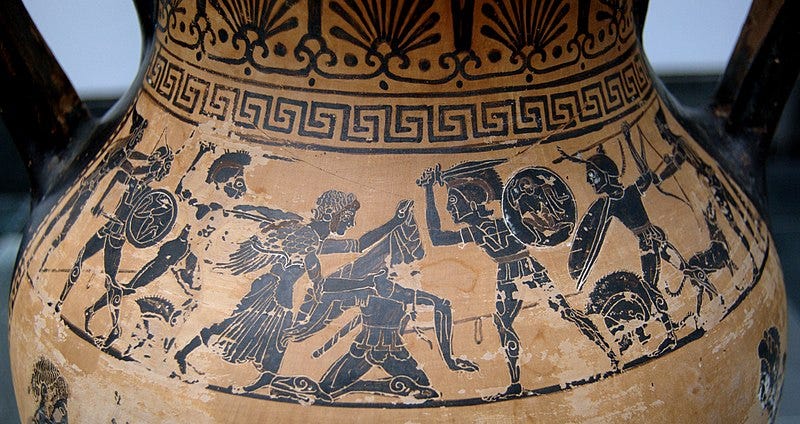

Book 5 presents the first full aristeia of the Iliad as Athena supports Diomedes’ destruction of the Trojan lines and opposition to the gods. Athena provides Diomedes the ability to see the gods and points him directly at Aphrodite. Diomedes and Athenelos are pitted against Aeneas and Pandaros–in the first of two significant testings of Aeneas in the Iliad–and Diomedes prevails. He wounds Aphrodite when she appears to rescue her son (Aeneas), replacing him with a fake version. To balance this weighing of different heroic traditions, Sarpedon, a son of Zeus, encounters Herakles’ son Tlepolemos. Sarpedon wins but is wounded and has to be saved. The flow of the action angers Athena and Hera who prepare to battle Ares. Zeus permits them to harry him and Diomedes wounds Ares as well. The book ends with the gods pulling back from the battle field, leaving space for the more human plots of book 6.

Each of the major scenes in book 5 contributes critically to some of the major themes I have noted to follow in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions. But the central themes I emphasize in reading and teaching book 5 are narrative traditions, heroism, and gods and humans. The paradigmatic consolation Dione offers Aphrodite when she is injured is structurally and thematically interesting, but the primary narrative entanglements of book 6 involve (1) Theomachy and (2) the characterization of Diomedes.

Theomachy and Homeric Gods

One of the chief themes of Book 5 is deferred theomachy. The gods engage in direct conflict elsewhere in the epic (most notably in books 13-15 and 20), but here we get a mix of theomachy by proxy (Diomedes wounding Aphrodite at Athena’s urging) and direct conflict (Athena vs. Ares) with Zeus intervening. The behavior of the gods in Homer, however, is crucial to understanding the epic’s messages about human beings.

The theme of theomachy (“war among the gods”) is integrated into the epic both to engage with its place in cosmic history and to appropriate themes from other traditions. For the latter, we have multiple echoes of earlier conflicts between the gods: the apostasy of Poseidon and Apollo that led to their service to build the walls of Troy (see books 7 and 12), reminders from Zeus of how powerful he is and how he punished them before (books 4, 8, 15) and reflections from other gods of how they settled and distributed their rights, alluding to moments that could be (but aren’t) represented in Hesiod’s Theogony.

While the Iliad is not explicit about it, divine-conflict deferred or avoided is central to the Trojan War myth writ large, especially around the character of Achilles and his mother Thetis (on which, no one has yet improved upon Laura Slatkin’s elegant The Power of Thetis). The story is deep, but easy to summarize: Prometheus had the secret knowledge of a nymph who would bear a son greater than his father, endangering the cosmos if Zeus or one of his brothers ended up the daddy in question. Zeus releases Prometheus from his bondage and torture in exchange for this information, leading to the arranged marriage of Thetis and Peleus.

So, at the center of Achilles’ apostasy from Agamemnon and his mother’s intervention on his behalf (triggering even more conflict among the gods) is the traditional threat that Achilles’ birth averted: upheaval among the gods. Nevertheless, as a narrative tradition seeking to encompass if not surpass all others, the Iliad still tries to include themes and motifs that would be proper both to the story that was never told (Zeus overthrown by a son) and those that were (Gigantomachies, Titanomachies, etc.)

Book 5 is the first time the gods really get into the action in the Iliad. They stage manage it in books 3 and 4, but finally get their hands dirty here. And a lot of what they do seems pretty embarrassing or even sacrilegious to modern audiences. This connects with the other main function of the gods and theomachy in the Iliad: to elevate the human condition.

Xenophanes, fragments 10-11

“Homer and Hesiod have attributed everything to the gods

that is shameful and reprehensible among men:

theft, adultery and deceiving each other

* * *

How they have sung the most the lawless deeds of the gods!

That they steal, commit adultery and deceive one another…Fr. 10

πάντα θεοῖσ’ ἀνέθηκαν ῞Ομηρός θ’ ῾Ησίοδός τε,

ὅσσα παρ’ ἀνθρώποισιν ὀνείδεα καὶ ψόγος ἐστίν,

κλέπτειν μοιχεύειν τε καὶ ἀλλήλους ἀπατεύειν.Fr. 11

ὡς πλεῖστ’ ἐφθέγξαντο θεῶν ἀθεμίστια ἔργα,

κλέπτειν μοιχεύειν τε καὶ ἀλλήλους ἀπατεύειν.

Heraclitus, fr. 42

“He used to say that Homer was worthy of being expelled from the contests and whipped along with Archilochus too.”

— —τόν τε ῞Ομηρον ἔφασκεν ἄξιον ἐκ τῶν ἀγώνων ἐκβάλλεσθαι καὶ ῥαπίζεσθαι καὶ ᾿Αρχίλοχον ὁμοίως

Diogenes Laertius, 8.21 (Lives of the Sophists)

“Hieronymos says that when Pythagoras went down into Hades he saw the ghost of Hesiod bound to a bronze pillar, squeaking, and that Homer’s ghost was hanging from a tree surrounded by snakes. They were being punished for the things they said about the gods. And in addition he saw men who were not willing to have sex with their own wives. This is the reason, that Pythagoras was honored by the inhabitants of Croton. Aristippos of Cyrene in his work Peri Physiologoi says that Pythagoras was given his name because he spoke the truth publically [agoreuô] no less than the Pythian oracle.”

φησὶ δ’ ῾Ιερώνυμος (Hiller xxii) κατελθόντα αὐτὸν εἰς ᾅδου τὴν μὲν ῾Ησιόδου ψυχὴν ἰδεῖν πρὸς κίονι χαλκῷ δεδεμένην καὶ τρίζουσαν, τὴν δ’ ῾Ομήρου κρεμαμένην ἀπὸ δένδρου καὶ ὄφεις περὶ αὐτὴν ἀνθ’ ὧν εἶπον περὶ θεῶν, κολαζομένους δὲ καὶ τοὺς μὴ θέλοντας συνεῖναι ταῖς ἑαυτῶν γυναιξί· καὶ δὴ καὶ διὰ τοῦτο τιμηθῆναι ὑπὸ τῶν ἐν Κρότωνι. φησὶ δ’ ᾿Αρίστιππος ὁ Κυρηναῖος ἐν τῷ Περὶ φυσιολόγων Πυθαγόραν αὐτὸν ὀνομασθῆναι ὅτι τὴν ἀλήθειαν ἠγόρευεν οὐχ ἧττον τοῦ Πυθίου.

There’s a tension between comments like those of Xenophanes and Heraclitus and the assertion by Herodotus (in book 2 of the Histories) that Homer and Hesiod Olympian Pantheon. I think a lot of this tension is a misunderstanding of what the gods in Homer are doing. They are simultaneously representations of divine beings (although not universal) and characters in a story. They do and do not reflect shared Greek beliefs about the gods. In addition, they serve as inducement for audiences to think about things like ‘fate’ and human agency. But they also serve to contrast with humans. The gods can do whatever they please because they face no consequences and live forever; by contrast, human beings face consequences for their actions and have a limited lifespan. The value of human life is thus actually increased by its scarcity and the importance of human choice and agency is all the more elevated by the fact that we can lose something so preciously limited at any moment. The gods end up looking somewhat distant and pathetic by comparison–but this is part of a general cosmic goal of justifying the separation between the worlds of gods and men.

People who focus on epic narrative have noted that the narrative worlds of gods and men overlap but are not coterminous. Divine players can learn about everything that goes on in the mortal realm, but mortals know only what is directly revealed to them. The external audience witnesses everything.

Why Diomedes?

Diomedes is a central figure in book 5’s allusions to theomachy and he helps defer these themes from god-on-god violence to god-by-proxy violence. Part of the reason Diomedes can function as a Theomahkos (on which, see Zoe Stamatopoulou’s great article cited below) is because he is also a substitute Achilles. But, because he is wholly mortal, he does not represent the same threat to the cosmic order. As covered a bit in posts on book 4, Diomedes is an important figure because of his place as a hero who was part of both the Theban and Trojan War traditions.

In the Iliad, his character is adapted to tell a different story about the way a young hero might be part of a larger coalition. There is of course a lot going on with Diomedes from a mythographical tradition, and he channels that as the Athena-aided hero who does great things in book 5; but he follows an important pattern in the development of his political acumen.

I have written several times on the importance of Diomedes in the Iliad’s political arc (sorry to be obnoxious, but Christensen 2009, 2015, and 2018 below). Here’s a table of his political/forensic actions in the epic.

(1) Diomedes (implicitly) witnesses the actions and speeches of Iliad 1-3

(2) Diomedes shows he knows the appropriate parameters for political and martial speech (Il. 4)

(3) Diomedes practices public speech and is acclaimed by all the Achaians in his refusal of Paris’ offer to return the gifts but not Helen (7.400-2). Acclamation (7.403-4):

(4) Diomedes practices public speech in criticizing Agamemnon and is acclaimed by all (9.50-1) but is criticized by Nestor for not reaching the télos múthôn (9.53-62). Acclamation (9.50-1)

(5) Diomedes practices public speech in reaction to Achilles’ rejection of the assembly (9.697-709) and is acclaimed by all the kings.

(6) Diomedes volunteers to go on a nocturnal spying mission during the council of kings and is encouraged by Agamemnon to choose any companion he wants regardless of nobility (10.219-39)

(7) Diomedes executes public speech at a critical moment and offers a plan (14.110-32). He is obeyed by all the kings and departs from the epic as a speaker.

Book 5, of course, stands outside of this narrative arc. Here, he carries out the ideal actions of a god-aided hero, fully replacing Achilles in the ranks of the Achaean warriors, but only for a short time. As you follow Diomedes throughout the epic, note that as soon as Achilles returns, Diomedes recedes from the stage entirely.

Some guiding questions

What is the relationship between Diomedes and Athena like in book 5?

How does the depiction of the gods in Book 5 contribute to their overall presentation in the Iliad?

How are stories outside the Iliad used in Book 5?

What is the impact of the violence in book 5?

Bibliography on Diomedes

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Andersen, Ø. 1978. Die Diomedesgestalt in der Ilias. Oslo.

Christensen, J. P. 2009. “The end of speeches and a speech’s end: Nestor, Diomedes, and the telos muthôn.”’ in K. Myrsiades, ed. Reading Homer: Film and Text. Farleigh.

Christensen, J. P. 2015. “Diomedes’ Foot-wound and the Homeric Reception of Myth.” In Diachrony, Jose Gonzalez (ed.). De Gruyter series, MythosEikonPoesis. 2015, 17–41.

Christensen, J. P. 2018. “Speech Training and the Mastery of Context: Thoas the Aitolian and the Practice of Múthoi” for Homer in Performance: Rhapsodes, Narrators and Characters, Christos Tsagalis and Jonathan Ready (eds.). University of Texas Press, 2018: 255–277.

Christensen, Joel P., and Elton T. E. Barker. “On Not Remembering Tydeus: Agamemnon, Diomedes and the Contest for Thebes.” Materiali e Discussioni per l’analisi Dei Testi Classici, no. 66 (2011): 9–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41415488.

Griffin, Jasper. 1986. “Homeric Words and Speakers.” JHS 106: 36–57.

Harries, Byron. “‘Strange Meeting’: Diomedes and Glaucus in ‘Iliad’ 6.” Greece & Rome 40, no. 2 (1993): 133–46. http://www.jstor.org/stable/643154.

HIGBIE, CAROLYN. “DIOMEDES’ GENEALOGY AND ANCIENT CRITICISM.” Arethusa 35, no. 1 (2002): 173–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44578455.

Martin 1989, R. The Language of Heroes, Ithaca 1989.

Morrison, James V. “The Function and Context of Homeric Prayers: A Narrative Perspective.” Hermes 119, no. 2 (1991): 145–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4476812.

Scodel, Ruth. "Homeric Attribution of Outcomes and Divine Causation." Syllecta Classica 29 (2018): 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1353/syl.2018.0001.

Stagakis, George. “DOLON, ODYSSEUS AND DIOMEDES IN THE ‘DOLONEIA.’” Rheinisches Museum Für Philologie 130, no. 3/4 (1987): 193–204. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41233632.

Stamatopoulou, Zoe. “Wounding the Gods: The Mortal Theomachos in the Iliad and the Hesiodic Aspis.” Mnemosyne 70, no. 6 (2017): 920–38. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26572880

Stamatopoulou, Zoe. “Wounding the Gods: The Mortal Theomachos in the Iliad and the Hesiodic Aspis.” Mnemosyne 70, no. 6 (2017): 920–38. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26572880

Turkeltaub, Daniel. “Perceiving Iliadic Gods.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 103 (2007): 51–81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30032218.

Some more on the Gods in Homer and Theomachy

A W. H. Adkins. ”Homeric Gods and the Values of Homeric Society.” JHS 92 (1972) 1-19.

W. Allan. “Divine Justice and Cosmic Order in Early Greek Epic” JHS 126 (2006) 1–35.

Burkert, Walter.1986. Greek Religion. 119-125.

G. M. Calhoun. “Homer’s Gods: Prolegomena”. TAPA 68 (1937) 24-25.

Jenny Strauss Clay. The Wrath of Athena: Gods and Men in the Odyssey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983.

—,—. The Politics of Olympus: Form and Meaning in the Major Homeric Hymns. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Erbse, Hartmut (1986). Untersuchungen zur Funktion der Götter im homerischen Epos. Berlin: de Gruyter

Friedman, Rachel. 2001. “Divine Dissension and the Narrative of the Iliad.” Helios 28:–118.

Griffin, Jasper. “The Divine Audience and the Religion of the Iliad.” The Classical Quarterly 28, no. 1 (1978): 1–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/638707.

Emily Kearns. “The Gods in the Homeric Epics.” In Robert Fowler (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Homer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, 59-73.

Lamberton, Robert. 1986. Homer the Theologian: Neoplatonist Allegorical reading and the Growth of the Epic Tradition. Berkeley and Los Angeles.

W. F. Otto. 1954. The Homeric Gods The Spiritual Significance of Greek Religion. Trans. M, Hadas.

Pietro Pucci. “Theology and Poetics in the Iliad.” Arethusa 35 (2002) 17-34

Turkeltaub, Daniel. “Perceiving Iliadic Gods.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 103 (2007): 51–81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30032218.

Preparatory Posts

Five Major Themes to Follow in the Iliad

Book-by-book posts

The Plan: Zeus’ Plan in the Iliad

Prophet of Evils: Reading Iphigenia in and out of the Iliad

Speaking of Centaurs: Paradigmatic Problems in book 1

Thersites’ Body: Description, Characterization, and Physiognomy in book 2

Heroic Appearances: What Did Helen Look Like?

(Hi, I'm amateur Ancient Greek enthusiast who really appreciates your posts and tweets.)

I'm sorry I can't intelligently comment on your post, but I recently read the Iliad in English for the first time cover to cover in a decade, and what leaped out to me about book 5 was the predominance of mentions of horses and chariots, which figure both in the Pandoras-Aeneas-Diomedes match up, and in the sub plot with the gods: Aphrodite asking Ares for his horses and going up in his chariot with Iris (Why does she, like Pandoras, not have a chariot?) just as Athena and Hera go down from Olympus in a chariot in a kind of unusual parallelism (while the wounded Ares returns to Olympus on his "swift feet." ) Also the horses of Laomedon come up a couple times and there's that weird part part where Athena asserts herself as Diomedes' chariot driver.