This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 21. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

In the last post on Iliad 21, I suggested that the supernatural violence of the book from when Achilles starts to fight the river Scamander to the realization of theomachy within the Iliad has the effect of overwhelming audiences, if inducing in them a ‘fog of war’ sensation as the events described get bigger, louder, more chaotic. The increase in intensity is both a function of Achilles’ rage and a narrative crescendo to help emphasize what comes next (the final meeting of Hektor and Achilles). As the noise quiets and the chaos simplifies, the narrative creates space for the speeches and encounters of book 22.

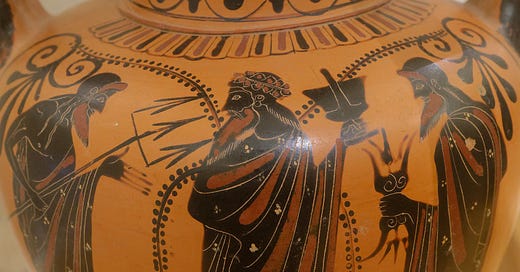

But the violence of 21 is about more still than building up the plot. It also dramatizes the danger intrinsic to a hero like Achilles and the cosmic disorder inherent to a world that mixes gods and mortals. One of the broader themes of the Iliad and the Odyssey together is the movement of the history of the divine world toward a settlement closer to the lives of Homer’s audiences. One metaphysical question attending Greek epic is why there are no demigods in their world.

As Barbara Graziosi and Johannes Haubold argue in their Homer: The Resonance of Epic, the Iliad and the Odyssey work in concert with other ‘Homeric’ poems (the Hymns) and the works of Hesiod to tell the story of the development of the cosmos up to the point of the basic perspective of the Archaic age in Greece. This process takes us from the creation of the world in Hesiod’s Theogony to the life of work and human intrigue described in the Works and Days. The Homeric narratives provide dramatic vignettes from steps along the way: The Hymns detail how individual gods came to occupy their sphere of influence and the epics tell about the end of the generation of heroes.

As Elton Barker and I discuss (probably too much) in Homer’s Thebes, Hesiod positions the end of the race of heroes as happening in the wars around Thebes and Troy. And, as I mentioned in a post on Zeus’ “plan”, a fragment from the lost epic, the Kypria confirms that this is all part of the cosmic order.

Hesiod, Works and Days, 161 165

Evil war and dread battle destroyed them (tous men),

some at seven-gated Thebes in the land of Cadmus,

when they fought for the flocks of Oedipus,

and others (tous de) when it had led them in their ships over the great deep sea

to Troy for lovely-haired Helen.καὶ τοὺς μὲν πόλεμός τε κακὸς καὶ φύλοπις αἰνὴ

τοὺς μὲν ὑφ’ ἑπταπύλῳ Θήβῃ, Καδμηίδι γαίῃ,

ὤλεσε μαρναμένους μήλων ἕνεκ’ Οἰδιπόδαο,

τοὺς δὲ καὶ ἐν νήεσσιν ὑπὲρ μέγα λαῖτμα θαλάσσης

ἐς Τροίην ἀγαγὼν ῾Ελένης ἕνεκ’ ἠυκόμοιο.D Schol. Ad Hom. Il. 1.5, Διὸς δ᾿ ἐτελείετο βουλή

“Some have claimed that Homer is riffing on another story. For people say that the earth was weighed down by an overpopulation of human beings, and since there was no sense of reverence among them, she asked Zeus to lighten her burden. First, Zeus arranged the Theban War right away. He used that to kill a lot of them, and then in turn he caused the Trojan War, because he listened to Momos’ advice. This is what Homer calls the plan of Zeus, since he was capable of destroying them all with lightning or floods (kataklysm). Momos prevented this, offering instead two plans: first, Thetis’ marriage to a mortal and then the birth of a beautiful girl. From these two events there would be a war between Greeks and barbarians which would result in unburdening the earth because so many were killed.

This story is told in the Kypria composed by Stasinus who says as follows (Cypria fr. 1)

There was a time when the countless mortal clans

Constantly weighed down the broad chest of the trampled earth.

When Zeus noticed, he felt pity and in his complex thoughts

Devised to unburden the all nourishing land of human beings.

He sowed the seeds of the great conflict around Ilion

To lighten that weight through death. And so at Troy

The heroes were dying and Zeus’ plan was being fulfilled.ἄλλοι δὲ ἀπὸ ἱστορίας τινὸς εἶπον εἰρηκέναι τὸν Ὅμηρον. φασὶ γὰρ τὴν Γῆν βαρουμένην ὑπὸ ἀνθρώπων πολυπληθίας, μηδεμιᾶς ἀνθρώπων οὔσης εὐσεβείας, αἰτῆσαι τὸν Δία κουφισθῆναι τοῦ ἄχθους· τὸν δὲ Δία πρῶτον μὲν εὐθὺς ποιῆσαι τὸν Θηβαϊκὸν πόλεμον, δι᾿ οὗ πολλοὺς πάνυ ἀπώλεσεν, ὕστερον δὲ πάλιν τὸν Ἰλιακόν, συμβούλωι τῶι Μώμωι χρησάμενος, ἣν Διὸς βουλὴν Ὅμηρός φησιν, ἐπειδὴ οἷός τε ἦν κεραυνοῖς ἢ κατακλυσμοῖς ἅπαντας διαφθείρειν· ὅπερ τοῦ Μώμου κωλύσαντος, ὑποθεμένου δὲ αὐτῶι γνώμας δύο, τὴν Θέτιδος θνητογαμίαν καὶ θυγατρὸς καλῆς γένναν, ἐξ ὧν ἀμφοτέρων πόλεμος Ἕλλησί τε καὶ βαρβάροις ἐγένετο, ἀφ᾿ οὗ συνέβη κουφισθῆναι τὴν γῆν πολλῶν ἀναιρεθέντων. ἡ δὲ ἱστορία παρὰ Στασίνωι τῶι τὰ Κύπρια πεποιηκότι, εἰπόντι οὕτως·

ἦν ὅτε μυρία φῦλα κατὰ χθόνα πλαζόμενα <αἰεί ἀνθρώπων ἐ>βάρυ<νε βαθυ>στέρνου πλάτος αἴης.

Ζεὺς δὲ ἰδὼν ἐλέησε, καὶ ἐν πυκιναῖς πραπίδεσσιν

κουφίσαι ἀνθρώπων παμβώτορα σύνθετο γαῖαν,

ῥιπίσσας πολέμου μεγάλην ἔριν Ἰλιακοῖο,

ὄφρα κενώσειεν θανάτωι βάρος. οἳ δ᾿ ἐνὶ Τροίηι

ἥρωες κτείνοντο, Διὸς δ᾿ ἐτελείετο βουλή.

I think that one helpful way to imagine book 21 is to see it as a rapid re-progression from the creation of the Universe and its potential theomachies to an explanation for why the gods are less involved in human affairs in ‘real life’ than in epic poetry. At the same time, the exploration of Achilles’ excess in his choosing of sacrificial victims, his refusal of a suppliant, and his onslaught against the river, emphasizes just how much suffering has been caused by a ‘hero’. The exchange of Poseidon and Apollo in the later half of the book emphasizes some of these themes.

Homer, Iliad 21.435-469

Then the powerful shaker of the earth addressed Apollo:

Phoibos: Why indeed do the two of us stand apart? It isn’t right

Now that the rest have begun. No, it would be more shameful

If we returned to the bronze-threshold of Zeus on Olympos without fighting.

Start, since you are the younger by birth. It isn’t right for me

Since I was born earlier and know more.

Fool, you have a thoughtless heart. You don’t remember

How many evils we two suffered over Ilion,

Alone of the goods, when we had to serve

Arrogant Laomedon for a year thanks to Zeus

For some promised pay. He ordered us around, telling us what to do!

I myself built the wall around the city for the Trojans,

I made it broad and very fine, so the city would be unbreakable.

And you, Phoibos, herded their ambling cattle

In the glens of forested and hilly Ida.

But when the year’s seasons produces the end of our contract,

Then that monster of a man cheated the two of us

Of all of our wages. And he sent us away with a threat.

He promised he would tie our feet and hands up

And sell us to islands far afield.

Then he threatened to cut both our ears off with bronze!

The two of us went back again with angry hearts

Enraged over the money he promised us but didn’t pay.

Now you are currying favor with his people and you don’t try

Along with us to make sure that the arrogant Trojans die out

Completely and horribly with their children and wives.”Far-shooting Apollo then answered him in turn:

“Earth-shaker, you would not describe me as wise

If I made war with you, at least, over the mortals,

Those unlucky creatures who grow like leaves

At one time flourishing into life, eating the fruit of the fields,

But then they shrink and wither. Come, let’s stop our fighting

As fast as we can. Let them fight on their own.”So he turned him back by speaking like this. For he was ashamed

To engage in violence with his father’s brother.”῝Ως φάτο, μείδησεν δὲ θεὰ λευκώλενος ῞Ηρη.

αὐτὰρ ᾿Απόλλωνα προσέφη κρείων ἐνοσίχθων·

Φοῖβε τί ἢ δὴ νῶϊ διέσταμεν; οὐδὲ ἔοικεν

ἀρξάντων ἑτέρων· τὸ μὲν αἴσχιον αἴ κ’ ἀμαχητὶ

ἴομεν Οὔλυμπον δὲ Διὸς ποτὶ χαλκοβατὲς δῶ.

ἄρχε· σὺ γὰρ γενεῆφι νεώτερος· οὐ γὰρ ἔμοιγε

καλόν, ἐπεὶ πρότερος γενόμην καὶ πλείονα οἶδα.

νηπύτι’ ὡς ἄνοον κραδίην ἔχες· οὐδέ νυ τῶν περ

μέμνηαι ὅσα δὴ πάθομεν κακὰ ῎Ιλιον ἀμφὶ

μοῦνοι νῶϊ θεῶν, ὅτ’ ἀγήνορι Λαομέδοντι

πὰρ Διὸς ἐλθόντες θητεύσαμεν εἰς ἐνιαυτὸν

μισθῷ ἔπι ῥητῷ· ὃ δὲ σημαίνων ἐπέτελλεν.

ἤτοι ἐγὼ Τρώεσσι πόλιν πέρι τεῖχος ἔδειμα

εὐρύ τε καὶ μάλα καλόν, ἵν’ ἄρρηκτος πόλις εἴη·

Φοῖβε σὺ δ’ εἰλίποδας ἕλικας βοῦς βουκολέεσκες

῎Ιδης ἐν κνημοῖσι πολυπτύχου ὑληέσσης.

ἀλλ’ ὅτε δὴ μισθοῖο τέλος πολυγηθέες ὧραι

ἐξέφερον, τότε νῶϊ βιήσατο μισθὸν ἅπαντα

Λαομέδων ἔκπαγλος, ἀπειλήσας δ’ ἀπέπεμπε.

σὺν μὲν ὅ γ’ ἠπείλησε πόδας καὶ χεῖρας ὕπερθε

δήσειν, καὶ περάαν νήσων ἔπι τηλεδαπάων·

στεῦτο δ’ ὅ γ’ ἀμφοτέρων ἀπολεψέμεν οὔατα χαλκῷ.

νῶϊ δὲ ἄψορροι κίομεν κεκοτηότι θυμῷ

μισθοῦ χωόμενοι, τὸν ὑποστὰς οὐκ ἐτέλεσσε.

τοῦ δὴ νῦν λαοῖσι φέρεις χάριν, οὐδὲ μεθ’ ἡμέων

πειρᾷ ὥς κε Τρῶες ὑπερφίαλοι ἀπόλωνται

πρόχνυ κακῶς σὺν παισὶ καὶ αἰδοίῃς ἀλόχοισι

Τὸν δ’ αὖτε προσέειπεν ἄναξ ἑκάεργος ᾿Απόλλων·

ἐννοσίγαι’ οὐκ ἄν με σαόφρονα μυθήσαιο

ἔμμεναι, εἰ δὴ σοί γε βροτῶν ἕνεκα πτολεμίξω

δειλῶν, οἳ φύλλοισιν ἐοικότες ἄλλοτε μέν τε

ζαφλεγέες τελέθουσιν ἀρούρης καρπὸν ἔδοντες,

ἄλλοτε δὲ φθινύθουσιν ἀκήριοι. ἀλλὰ τάχιστα

παυώμεσθα μάχης· οἳ δ’ αὐτοὶ δηριαάσθων.

῝Ως ἄρα φωνήσας πάλιν ἐτράπετ’· αἴδετο γάρ ῥα

πατροκασιγνήτοιο μιγήμεναι ἐν παλάμῃσι.

One of the striking things about this passage is the repeated language of evaluation or judgment: Poseidon (and then the narrator) are concerned with shame and propriety. It may seem strange that Poseidon spends so much time describing their mistreatment at the hands of Laomedon, but it works thematically well for this section. First, it shows how the Trojans failed a test of theoxeny (when gods go in disguise to test people); second, it demonstrates that gods themselves suffer pain from human beings; and, third, I think it also implies that humans suffer from these exchanges as well. Imagine how much less suffering there would be if the Trojans’ did not possess a wall built by Poseidon!

While Poseidon focuses on the insolence of the Trojans, extending the behavior of the long-gone forefather to the entire city, Apollo steps quickly away. He does not emphasize their shame, but his own prudence, or imprudence were he to fight Apollo for the sake of mortals. In a way, Apollo echoes Glaukos in book 6 of the Iliad when he compares human generations to the leaves. (Note the similar battlefield context and the use of the image of brevity if not futility to disengage from a fight through speech.) But this also echoes Sarpedon’s speech to Glaukos in book 12 when he says they must fight and die because they are mortal. The general argument of the Iliad—and I think a theological/metaphysical theme for the epic world—is that humans receive glory because they sacrifice what they have in short supply. Human life can have morality, shame, duty, and meaning because there are consequences that cannot be surmounted by time.

For the gods, whose lives cannot change because the cosmos is fixed in place by Zeus’ order, there’s no advantage from fighting with or about mortals any more. The gods, from the Homeric perspective, can gain no honor; they can not actually change. The only thing they receive any longer from mingling with human beings is pain—the loss of honor, as in Poseidon’s shaming by Laomedon; the physical pain Aphrodite feels when Diomedes wounds her in book 5; and, most of all, the emotional pain of loss Zeus feels for the death of Sarpedon alongside the terrible grief Thetis faces in empathizing with her son and anticipating his death.

Apollo, the god who started the divine actions in the Iliad, is shown here declaring he has had enough. And while the speech is short, Poseidon agrees. They leave the battle to let the mortals work it out for themselves as the gods watch from the distance in lives of eternal ease.

A short bibliography on Homeric Gods

A W. H. Adkins. ”Homeric Gods and the Values of Homeric Society.” JHS 92 (1972) 1-19.

W. Allan. “Divine Justice and Cosmic Order in Early Greek Epic” JHS 126 (2006) 1–35.

Burkert, Walter.1986. Greek Religion. 119-125.

G. M. Calhoun. “Homer’s Gods: Prolegomena”. TAPA 68 (1937) 24-25.

Barbara Graziosi and Johannes Haubold. Homer: The Resonance of Epic. London: Duckworth, 2005.

Jenny Strauss Clay. The Wrath of Athena: Gods and Men in the Odyssey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983.

—,—. The Politics of Olympus: Form and Meaning in the Major Homeric Hymns. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

—,—. Hesiod’s Cosmos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003

Erwin Cook. The Odyssey in Athens: Myths of Cultural Origins. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995.

E. R. Dodds. The Greeks and the Irrational. Berkeley, 1951.

Erbse, Hartmut (1986). Untersuchungen zur Funktion der Götter im homerischen Epos. Berlin: de Gruyter

Barbara Graziosi and Johannes Haubold. Homer: The Resonance of Epic. London: Duckworth, 2005.

Christopher Gill. Personality in Greek Epic, Tragedy and Philosophy: The Self in Dialogue. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Jasper Griffin. Homer on Life and Death. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Heiden, Bruce 2002. “Structures of Progression in the Plot of the Iliad.” Arethusa 35 (2002) 237-54.

Emily Kearns. “The Gods in the Homeric Epics.” In Robert Fowler (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Homer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, 59-73.

Lamberton, Robert. 1986. Homer the Theologian: Neoplatonist Allegorical reading and the Growth of the Epic Tradition. Berkeley and Los Angeles.

N. J. Lowe. The Classical Plot and the Invention of Western Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

W. F. Otto. 1954. The Homeric Gods The Spiritual Significance of Greek Religion. Trans. M, Hadas.

Pietro Pucci. “Theology and Poetics in the Iliad.” Arethusa 35 (2002) 17-34.

Naoko Yamagata. Homeric Morality. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1994.