This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations. Don’t forget about Storylife: On Epic, Narrative, and Living Things. Here is its amazon page. here is the link to the company doing the audiobook and here is the press page. I am happy to talk about this book in person or over zoom.

Book 21 continues the fierce violence that followed Achilles’ return to battle. If the central ‘set piece’ of book 20 is Achilles’ encounter with Aeneas and the clashing of those traditions, the central theme of book 21 is about the extent of Achilles’ rage, how it dehumanizes others and himself. The narrative explores this through Achilles’ refusal to ransom Lykaon and his struggle with the river god.

Both of these features are anticipated by a scene at the beginning of the book that also resonates themes from the beginning of the epic. As Achilles presses the Trojans into the river, he gets worn out “murdering people” and stops to select some of the Trojans for a sacrifice to e made later in the epic.

Iliad 21.21-33

“So the Trojans were cowering in the streams under the banks

Of the terrible river. But when Achilles wore out his hands murdering people,

He chose twelve youths still alive from the river

To be a bloodprice for Patroklos, the dead son of Menoitious,.

He led them away stunned like fawns.

He bound their hands behind them in the well-cut belts

they were carrying themselves for their soft tunics.

He handed them over to his companions to lead to their hollow ships.

But then he went back at it again, eager to kill.”ὣς Τρῶες ποταμοῖο κατὰ δεινοῖο ῥέεθρα

πτῶσσον ὑπὸ κρημνούς. ὃ δ’ ἐπεὶ κάμε χεῖρας ἐναίρων,

ζωοὺς ἐκ ποταμοῖο δυώδεκα λέξατο κούρους

ποινὴν Πατρόκλοιο Μενοιτιάδαο θανόντος·

τοὺς ἐξῆγε θύραζε τεθηπότας ἠΰτε νεβρούς,

δῆσε δ’ ὀπίσσω χεῖρας ἐϋτμήτοισιν ἱμᾶσι,

τοὺς αὐτοὶ φορέεσκον ἐπὶ στρεπτοῖσι χιτῶσι,

δῶκε δ’ ἑταίροισιν κατάγειν κοίλας ἐπὶ νῆας.

αὐτὰρ ὃ ἂψ ἐπόρουσε δαϊζέμεναι μενεαίνων.

I comment at further length on the sacrifice in a post on book 23. A scholion connects this action to book 23, but with some concern explaining what exactly Achilles is doing:

Schol. Ad Hom. Il. bT/b 21.27 ex

“He selected twelve youths” because he is going to prepare them for a sacrifice called a dozen. This provides a great excess through it, that he decides to select captured warriors, mentioning how many and of what sort, and then that he binds them all together, their hands stretched out as if they are enslaved.

Certainly, his companions are assisting him in all these things, but the whole of it comes from him.

δυώδεκα λέξατο <κούρους>: ὡς εἰς θυσίαν μέλλων παριστάνειν τὴν καλουμένην δωδεκάδα. μεγάλην δὲ τὴν ὑπεροχὴν διὰ τούτου παρίστησιν, ἐπιλέξασθαι αὐτὸν τοὺς αἰχμαλώτους λέγων οἵους καὶ ὅσους ἐβούλετο, εἶτα καὶ τούτους καθ' ἕνα συνδῆσαι, ὥσπερ ἀνδράποδα προτείνοντας τὰς χεῖρας (cf. Φ 30). τοίνυν συνυπούργουν αὐτῷ οἱ ἑēταῖροι ἐν τούτοις πᾶσι, τὸ δὲ ὅλον ἦν τὸ αὐτοῦ.

In the post on book 23, I emphasize the strangeness of the sacrifice and how it fits into the Iliad’s narrative arc. When I returned to this passage, one of the things that stood out for me was the phrase “bloodprice for Patroklos”. The word poinē is related to our English word “penalty” from the Latin borrowing poena. Here, simply expressed in the grammar of the “youths as a ποινὴν Πατρόκλοιο,” a penalty for Patroklos.

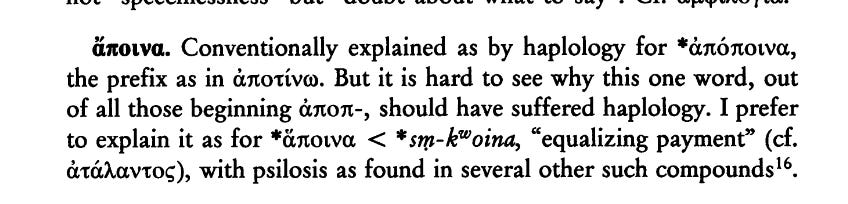

From Beekes Etymological Dictionary of Ancient Greek.

Poinē has important thematic resonance for the Iliad. In her insightful monograph, Ransom, Revenge, and Heroic Identity in the Iliad, Donna Wilson argues that Homeric characters distinguish between two different kinds of compensation: apoina, which is what Chryses offers at the beginning of the epic to ransom his daughter back (1.13), is a kind of exchange price that does not deprive the one who accepts it of honor, since the notional esteem of the exchange is more or less equal.

Poinē, on the other hand, is a price paid that detracts from the honor or cultural position of the one who grants it because they receive nothing in return. By giving poinē, a party concedes that they have done wrong or owe a debt that subtracts from their esteem and repairs or increases that of the recipient. Poinē is thus always cosmically destabilizing whereas apoina seeks to keep the universe balanced.

Wilson’s classic example of this is by way of explaining some of the conflict in Iliad 9: when Agamemnon sends the embassy in book 9, he instructs them to offer apoina (9.120), which would repair their relationship by making some amends, but would not signal a loss to Agamemnon. Achilles, Wilson argues, sees the harm to his position as deep enough to require poinē (although he does not articulate it as such).

What the Iliad does show, however, is that the breakdown in social exchange marked by the failure of Agamemnon to accept apoina from Chryses lasts until Achilles restores the stability of the system by accepting apoina instead of poinē from Priam in book 24 (24.139, 502, 579, 594, 686). In between these two events, there are several moments that translate the social failure of Agamemnon’s actions to start the epic to the larger context of the Iliad and the exceptional world of the Trojan War.

Consider the oath in book 3:

Il. 3.288-291

“But if Priam and Priam’s sones are not willing

To pay me back after Alexandros has fallen,

Then I will fight on afterward, staying here

For the sake of a bloodprice, until I come to the end of war.”εἰ δ' ἂν ἐμοὶ τιμὴν Πρίαμος Πριάμοιό τε παῖδες

τίνειν οὐκ ἐθέλωσιν ᾿Αλεξάνδροιο πεσόντος,

αὐτὰρ ἐγὼ καὶ ἔπειτα μαχήσομαι εἵνεκα ποινῆς

αὖθι μένων, ἧός κε τέλος πολέμοιο κιχείω.

Here, the oath marks the violence of war as the means to re-balance esteem and worth by demanding a penalty from the Trojans for theft of Helen. It would not be enough for the Trojans to return the woman and the stuff, instead, they have to give up something of themselves, something intangible but costly, to compensate the Greeks for the loss to their esteem done by Paris’ actions.

Even this system, however, shouldn’t commend Achilles’ internecine violence. Ajax attempts to connect the personal ethics of blood prices to the political when he speaks in the embassy.

Il. 9.632-638

“Pitiless man: someone may even accept a bloodprice

For a murdered relative, even when his own son has died.

And then the other remains in his country, once he paid back a lot.

But this man’s heart and proud spirit prevents him

From accepting a bloodprice: the gods gave him an intractable and evil

Heart in his chest over a girl, only a girl.νηλής· καὶ μέν τίς τε κασιγνήτοιο φονῆος

ποινὴν ἢ οὗ παιδὸς ἐδέξατο τεθνηῶτος·

καί ῥ' ὃ μὲν ἐν δήμῳ μένει αὐτοῦ πόλλ' ἀποτίσας,

τοῦ δέ τ' ἐρητύεται κραδίη καὶ θυμὸς ἀγήνωρ

ποινὴν δεξαμένῳ· σοὶ δ' ἄληκτόν τε κακόν τε

θυμὸν ἐνὶ στήθεσσι θεοὶ θέσαν εἵνεκα κούρης

οἴης….

Ajax is making the extreme argument that a man who has done wrong can still stay in his community if he accepts that he has done wrong and pays the price needed to satisfy the family of a dead loved one. Such a possibility makes it even more surprising, to Ajax, that Achilles is being so hard hearted about apoina when the conflict is about “only a girl” (like the Trojan War itself). But, as Wilson notes, Ajax has misread what Achilles is looking for: Achilles wants to harm the person who harmed him. He wants Agamemnon to lose as much as he wants to win.

A ransom exchange is in game theory terms a positive sum game because everyone keeps their social esteem and, in my opinion, gains benefit by not engaging in violence. The system of poinē, however, is zero sum: you cannot receive a penalty without someone else granting it. This is the torturous logic of most of the Iliad: When Agamemnon demands that his brother not ransom a prisoner in book 6 or when Achilles refuses to release Lykaon in 21, the logic is that of the whole Trojan War: retribution requires a form of justice that takes from others to penalize them for doing harm first.

If poinē requires retributive justice, could we pose the system of apoina as restorative or reparative? When I teach myth and the Iliad to students I focus on hospitality and exchange as being the only ethical systems outside of the confines of the city the the violence of the state. The Iliad shows that a system of exchange that preserves social position rather than harms it is, perhaps, preferable to one that necessarily damages others. But the extent to which this applies to the world outside the poem is for the audience to consider.

Part of the interest of both Homeric epics–and, indeed, Greek myth in general, is how to stop cycles of violence and revenge. A non-retributive system of justice is likely a good answer, but it leaves open the question of personal angst and grief: how many parents could truly accept a mere apoina for the loss of a child? This cuts to the heart of the Iliad’s questions about the balance of personal grief and political well-being. Note, that however much the actions of Achilles and Priam have political features, they remain at heart an agreement between individuals who don’t wholly reevaluate the logic of the war.

Iliad 21

What Do You Do With a Problem Like Achilles? Introducing Iliad 21: Achilles; Sacrifice; narrative judgment

You're Gonna Die Too, Friend: Achilles' Speech to Lykaon in Iliad 21: Achilles and Lykaon; Surrogacy; Death; Gilgamesh and Iliad

They're Just Not That Into Us: On Mortals and Gods in Iliad 21: Gods and mortals; Cosmic history; Hesiod

Bibliography

West, Martin L. “Some Homeric Words.” Glotta 77, no. 1/2 (2001): 118–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40262722.

Donna F. Wilson, Ransom, revenge, and heroic identity in the Iliad. CUP 2003,